The body as a bearer and object of design

DS.WRITER:

Christina Ioakeimidou

Central Image: Objects of Desire (Pleun van Dijk) | Source: images.squarespace-cdn.com

The body is the principal symbol of harmony since its individual parts are connected to create a whole. It regulates our lives and movements, giving life to any living being. The same is observed in design since it is nothing but the smooth and perfect coexistence of the individual elements that create the final result. But can the body act as a means of design? Can we consider the use of patterns in various objects or works of art, which refer to the body, as symbols? The answer to these questions seems to be affirmative.

The body as design’s everlasting “partner”

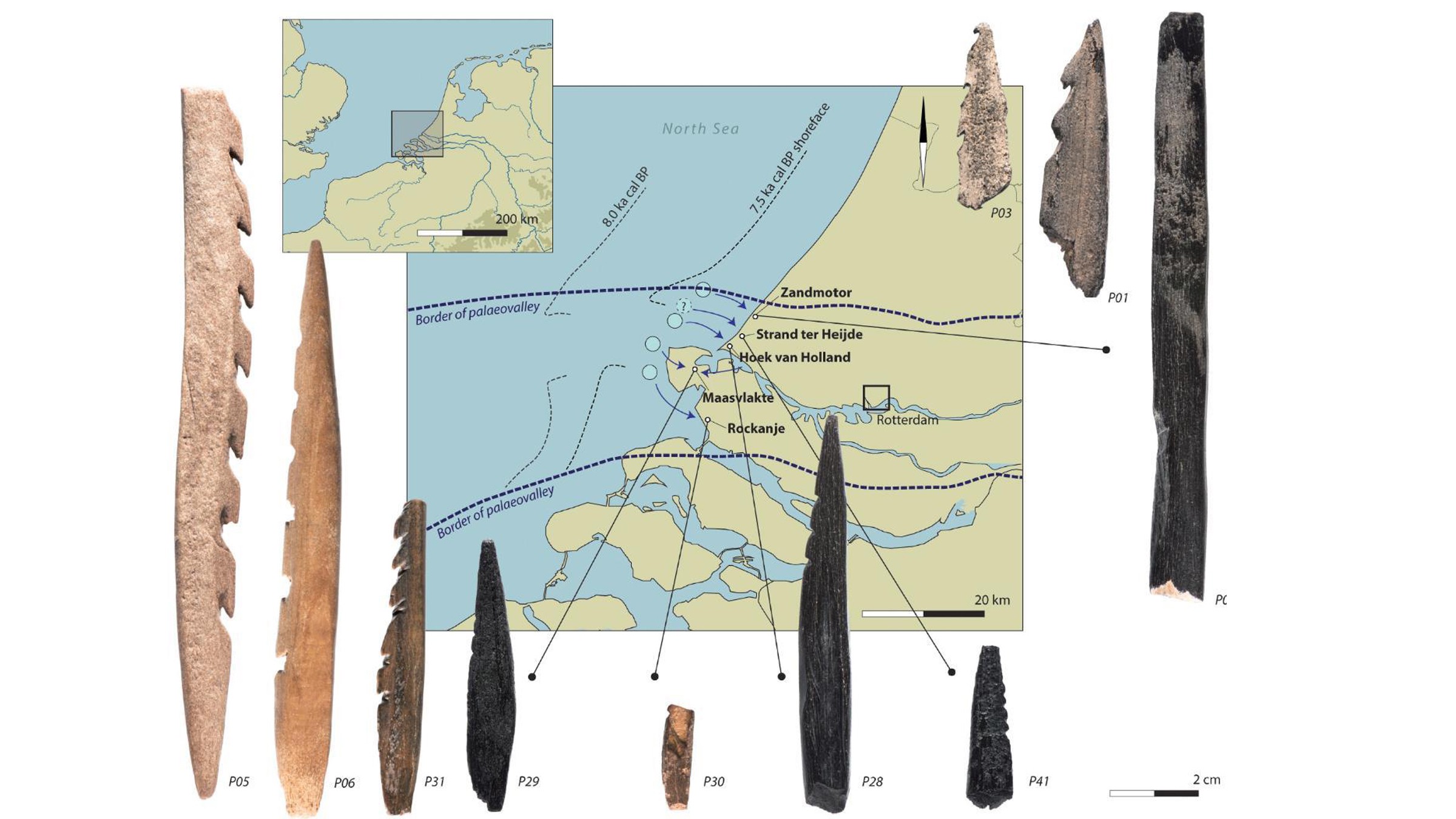

The body always constituted a sort of compass for designing objects, since prehistoric times. Thanks to archaeological research, objects like tools or weapons have been found, made not only from natural materials (rocks, shells, amber etc.) but from body parts as well - most of the time from animals but there are also findings of human bones. However, these kinds of findings are rarely characterised as utilitarian objects since in most cases they are objects of symbolic "use". Examples of such objects are found in many regions of the planet. Hundreds of blade-shaped bone objects have also been found in the North Sea, dating to the time of the last foragers (8,000-11,000 years ago). Obviously, the size and delicacy of these finds make their use as weapons difficult, inferring instead that they were objects used in ceremonies or had other cultural value, such as indicating the superior power of their owner as well as the intent to demonstrate one’s sexual status that served reproduction.

Prehistoric weaponry made from human bones and their place of discovery (Europe). | Image source: cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net

Of course, these specific findings do not obscure the importance of the relationship between body and design. After all, according to Darwin, decorativeness also bears the concept of sexual selection, which complements the mostly instinctive natural selection. He even devoted a large part of his work The Descent of Man to the justification of this view.

This jewelry is made of amber and three azure glass beads (Mycenaean era tomb) | Image source: leivithrapark.gr

But the attempt to highlight the body, many times changing it in the process, was a frequent practice that connected the individual with nature and -by extension- with the evolutionary process itself. Consequently, the effort to self-configure the human body, which can still be encountered in various tribes today - like in the case of the women in Burma -, was considered a clearly painful but necessary process of evolution. Here, we could mention the modern practice of changing one’s external appearance for aesthetic reasons. Therefore even the loss of hair, based on Darwin’s theory, was understood as part of this "decorative evolutionary process", despite the disadvantages it could cause in the survival of humans.

However, this total reconfiguration of specific parts of the body may bear different connotations per case, which does not allow us to generalise the root causes of the phenomenon, resulting in some stereotypical, perhaps, explanations.

E. Burma woman with bronze hoops around her neck, symbolising beauty (but also perhaps oppression) | Image source: mir-s3-cdn-cf.behance.net

But how can the human body itself be reduced to an artefact and what is the meaning bestowed to it over the centuries?

The body as a decorative pattern

During Greek classical antiquity, the naked body was the most frequent pattern in decoration. However, the subject matter seems to vary depending on the use and symbolic meaning of the object. Thus, on grave markers that were to highlight the power and status of the deceased, we have the presence of naked or semi-naked male bodies -most often in idealised form- so that the robust nature of the buried can be seen. In contrast, when it comes to a dead woman, the figures are clothed, more contemplative, exuding peace and tranquillity. We could perhaps cautiously say that, in this way, the high reliefs were the reason for an initial separation of the sexes and their respective "properties", which would later lead to the sexualization of the female body.

Grave marker (stele), c. 410-400 BC | Image source: archaiologia.gr

With the passage of time and the spread of Christianity, the body is reduced to a "forbidden fruit", with its naked depiction considered unthinkable until the Renaissance. Then the body is once again present in art, following classical standards. But the redesign of the body raises questions as to who will be depicted and in what way, with the female figures almost always called by the names of ancient deities to renounce the "shame" of their public display. The paradox, however, is that the most descriptive example of this view comes not from Renaissance artists but from 1863. Claude Manet's well-known painting, Olympia, is perhaps the most accurate example of highlighting sexual attraction, without however directly referring to something familiar and every day.

Olympia, E. Manet, 1863. (Musée d'Orsay, Paris) | Image source: upload.wikimedia.org

The painting, essentially, depicts the Parisian society of the 19th century, projecting two women, almost psychosomatically objectified. Lying on a recliner, surrounded by expensive fabrics and ornaments, with gold jewellery in her hand and pearl earrings, Olympia* now has the same financial comfort as her spectator-client, wearing all the "symbols of her wealth". The only thing that might remind us of her relationship with the client-spectator is the jewel around her neck, perhaps a remnant of her "previous" life. On the other hand, the woman of African descent is shunned to the side, her face lost in the dark background, as she might have been in the public life of the time when her only purpose for existence was in the back rooms of the house.

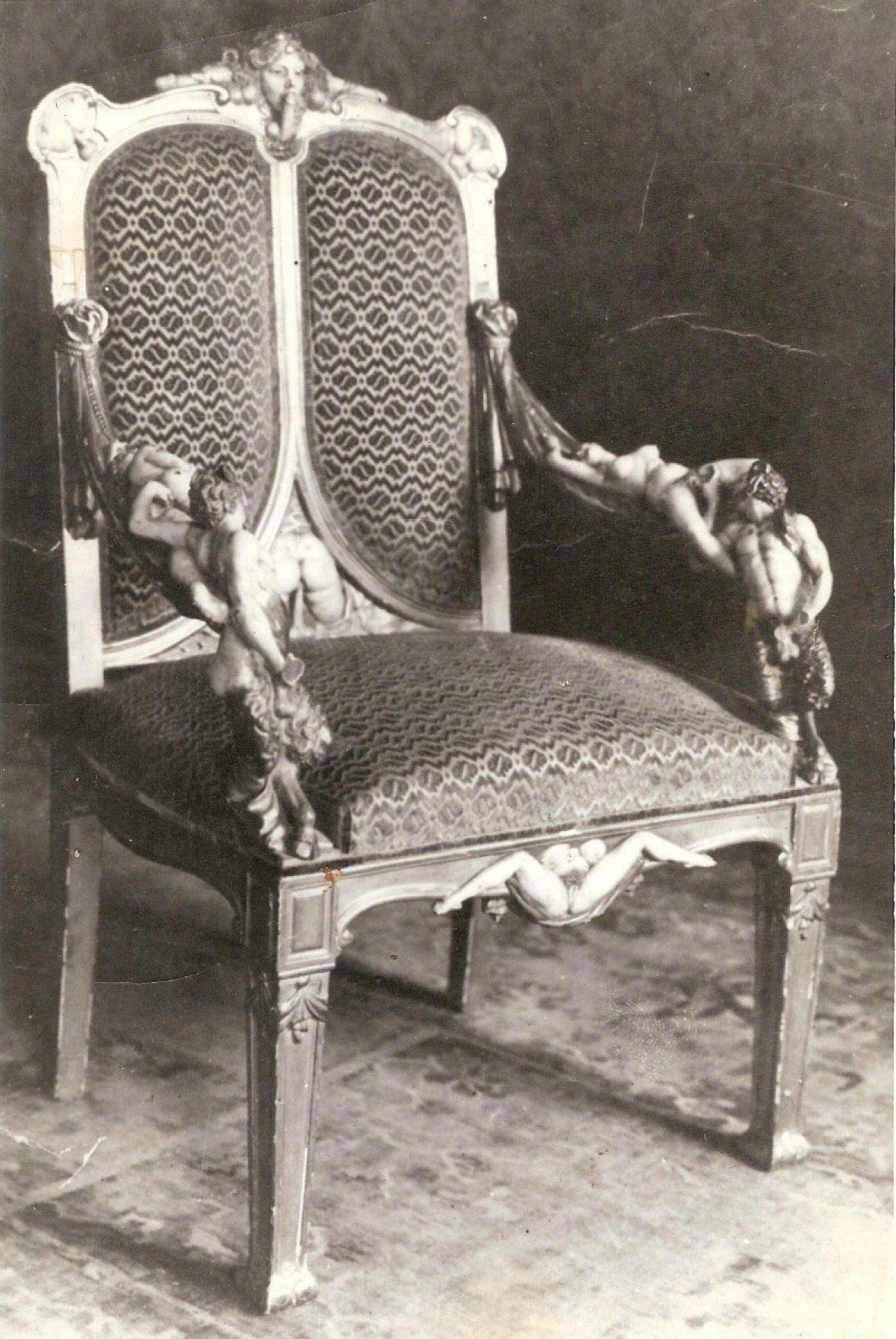

However, male sexuality has repeatedly been the subject of artistic works and objects intended for the decoration of spaces. Such an example comes to us from the Tsarist court of the 18th century. The owner of this somewhat unique piece of furniture appears to be Catherine II of Russia.

Armchair from the personal collection of Catherine The Great (18thcentury) | Image Source: 1.bp.blogspot.com

The objects in question, which appear to have belonged to the empress's personal collection, were placed in a secret room where she hosted her various lovers. But would it be wise to consider the patterns of both the furniture and the room that hosted it as a mere decorative suggestion by Catherine? The answer to the question could be given if we take into account, once again, the body as a tool for indicating sexuality as well as socio-political power. Therefore, by thinking about the status of her love partners and their promotion or removal from positions of power, we could reduce the use of this particular decoration as a means of instrumentalizing the body. It is possible, then, that these tsarist pieces of furniture have exactly the same connotations as the Parisian Olympia or that they can be characterised as ancestors of the later furniture by Allen Jones, who mainly used the female body in his -for many extremely sexist- compositions, creating furniture or installations, which provoked public opinion.

Of course, a lot has changed in modern and contemporary design and art in general, mainly the way of visualising the body. Now, criticism has become the main focus of designers, regardless of their artistic orientation.

The body as a means of revision

Beginning with Dada, Hannah Hoch's Beautiful Girl (1920) is understood as a first attempt to deconstruct the body. Modern art raises its voice in matters of redefining sexuality and identity. Several years later, Marina Abramović, through body art, used the body as a sign of inscription, as a channel between artist and audience, where subjectivity is reinvented. In this way, the relationship between the performer and the viewer acquires a different aspect, with subjectivity mutating into a total experience and perception of identity.

Freeing the body, 1975 (Marina Abramović) | Image source: artbasel.com

However, art concerning the body and its visual distortion does not stop at Abramović. With the widespread "consumption" of plastic surgery, more and more artists explore this phenomenon as the subject of their works. From Lucy McRae and the association of beauty with an algorithm that "regulates" hyper-perfection - after all, dystopian beauty is present in her installations - to Bart Hess, who with his 2016 installation, Digital Artifacts, highlighted the skin as a "personal uniform,"- an essentially second skin that perfectly fits each individual body. Pleun van Dijk moves in the same artistic direction, with her sculptures, Objects of Desire, underlining the deep relationship between man and technology, working on them through an algorithm. Van Dijk follows two different phases, first creating her sculptures, which are then read by an algorithm. In this way, the deeper relationship that the artist has with her creations is more objectively clarified. The second phase is related to a generative algorithm, which, with the help of Machine Learning (ML), was able to arrive at the design of unspecified sculptures, imitating human genitalia and sex toys, sourced from a collection of corresponding collected photos.

Objects of Desire (Pleun van Dijk) | Image Source: images.squarespace-cdn.com

Moreover, apart from the technological discussion, the body is what gives birth to feelings, and memories. With this thought, we arrive, initially, at the somewhat eerie gaze of Daisy Collingridge. The latter, together with her Squishies, constructs a world in which the body is nothing more than the container of the individual, removed from archetypes. It is a colourful construction, which reflects the personality of everyone, exactly where they are, depicting externally the inner parts of the body.

All of the Squishies embracing each other (Daisy Collingridge) | Image source: yatzer.com

A breakthrough for the "redesign" of the body was the period of increase in aesthetic interventions. Now everyone can transform themselves, sometimes freeing them from their inner insecurities. Of course, one would be remiss if one did not wonder whether the increasing use of filters on social media has influenced this new trend in the perception of what a body is. Based on this thought, the well-known house of Balenciaga presented an ambiguous spectacle at the 2020 show, attaching additional pieces of "skin" to the models’ faces. Obviously, Demna Gvasalia’s intent, however well-meaning it may have been - and it could be seen as a somewhat misplaced and exaggerated mockery of plastic surgery -, generates questions on the position of this specific brand and generally of the field of fashion, regarding such interventions.

Balenciaga fashion show Spring/Summer 2020 | Image Source: images.squarespace-cdn.com

Finally, Shalva Nikvashvili’s works for the project Almost Beautiful, prove, in an intelligent but at the same time bitter way, that the standardisation of beauty by no means guarantees happiness. For him, beauty is the memory and emotions that are registered on the face. With the coming erasure of reconfiguration, these are lost, they melt away.

Shalva Nikvashvili (from The Why Not Gallery) | Image source: static.wixstatic.com

From the latter examples, we can understand that the body has stood throughout time as a means of demonstrating power but also of criticizing it, often disregarding the social imperatives of each society or even promoting them. However, it will always be a means of remembering, and connecting with the past, but also an opening to the technological future, which can be redesigned just like the body. We cannot hide our opinion that the future is uncertain in relation to the possibility of relating body and art. Only one thing is certain. The new movements that highlight diversity and its acceptance will create new currents in the practice of design.

*The real names of the prostitutes of the times were changed so that the workers would not be recognised by those around them. Names referring to ancient deities were the most common, a practice also found in painting, where the female figures were mainly dubbed "Venus".

Further reading and Sources:

B. Colomina & Μ. Wigley. Αre we human? notes on an archaeology of design (Lars Müller Publishers).

N. Korzhov & A. Kovalenko (2013). Myanmar’s neck ring women. From: aljazeera.com.

T. Hölscher. Κλασική αρχαιολογία: Βασικές γνώσεις (University Studio Press).

A. Χαραλαμπίδης. Η Ιταλική Αναγέννηση. (University Studio Press).

A. Bridget. (2020). Ancient European Hunters Carved Human Bones Into Weapons. From: smithsonianmag.com.

Two Rare Photographs of the X-Rated Furniture of Catherine the Great. From: vintagenewsdaily.com

“Olympia” Manet – An Analysis of Édouard Manet’s Olympia Painting. From: artincontext.org.

C. Delistraty (2019). Modernism’s Debt to Black Women. From: theparisreview.org.

A. McNearney (2019). The Mystery of Catherine The Great's 'Erotic Cabinet'. From: thedailybeast.com.

C. Demaria (2004). The Performative Body of Marina Abramović: Rerelating (in) Time and Space.

Hannah Höch. From: widewalls.ch.

Α. Winston. Anna Aagaard Jensen's A Basic Instinct chairs reinvent "manspreading" for women. From: dezeen.com.

L. Laventi. Balenciaga Sends Extreme Cheekbones and Blown-Up Lip Prosthetics Down the Runway in Paris. From: vogue.com.

Pleun van Dijk: pleunvandijk.com.

Bart Hess: barthess.com.

Lucy McRae: lucymcrae.net.

Balenciaga fashion show Spring/Summer 2020, at: youtube.com.