Public space: Safer cities through inclusivity

DS.WRITER:

Christina Ioakeimidou

Image Source: cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com

For several decades now, the increasingly urgent need to develop safe spaces for social groups that are victims of harassment on the streets of cities has been acknowledged. Women, children and especially members of the LGBTQ+ community are likely to receive varying degrees of violent behaviour. So, the need to remodel existing public spaces or create areas such as Gayborhoods became prominent. In fact, these neighbourhoods have even become symbols of the cities to which they belong. Soho in London, Greenwich Village in New York, Schöneberg in Berlin and the Athenian Gazi are some of the neighbourhoods that have officially joined the list of The Gayborhood Foundation and are reference areas for social life and, especially, the nightlife of the aforementioned cities. But is the initiative of the community itself enough to prevent the spread of violence and strengthen the protection of its members? Should the respective public institutions ensure the acceptance of LGBTQ+ citizens through other initiatives?

Gayborhoods as places for the community to come up for air?

Gayborhoods seem to be more than just neighbourhoods. They are places that were created, as early as the 1950s, to give voice and opportunities to people who were historically excluded from the life of the cities to which they belonged. The benefits for queer people don’t seem to be strictly social (easier development of interpersonal relationships, freedom of expression and social acceptance) but also economic since the upgrading of areas that were previously unfairly considered ghettos is encouraged through investments and the possibility of their local administration. In other words, the residents can potentially live without fear and develop professional activities, thereby defining the economic course of the specific areas.

However, despite the positives such as freedom of expression and convenience (good transport links to the rest of the city, access to bars and low rents), Gayborhoods seem to be changing drastically. The ever-increasing investment activity of wealthier gay white men led to rising costs of living and the gradual marginalization of members of the community who did not belong to the upper social classes. In addition, the transformation of once degraded areas into hangouts for gay and straight people has tainted the character of neighbourhoods such as London's Soho, where unusually high levels of homophobia are noted.

Soho, London | Image Source: theideasmanifestor.com

Obviously, no matter how different the character of these areas may become, they do not cease to be places where the full acceptance of members of the LGBTQ+ community is the main axis around which the social life of its residents and patrons develops. However, it is clear that the development of Gayborhoods should not be the sole action for the protection and better quality of life for the queer community but an addition to a centrally planned development.

Public safety, visibility, inclusivity

The imperative of inclusion has been acknowledged by several states worldwide, with LGBTQ+ flags placed prominently outside many public buildings. In fact, and in collaboration with public bodies of various cities, the Rainbow Cities Network has been developed with the aim of aiding the placement of flags in public spaces around the world. Additionally, in many queer areas, the male figure on traffic lights has been replaced by two same-sex couple figures.

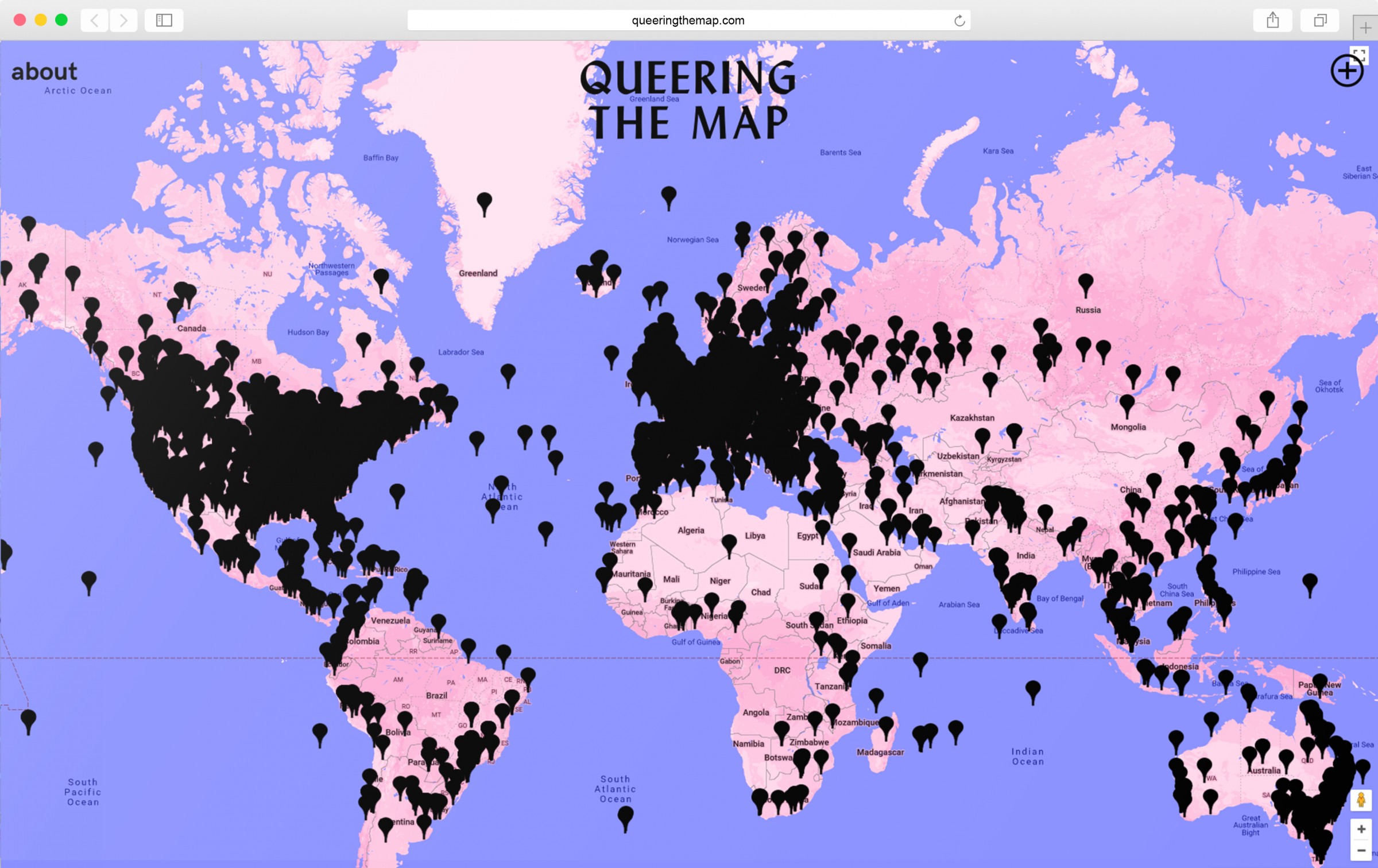

Yet another initiative that promotes community solidarity is a project by Lucas Larochelle, a queer Canadian. Queering the Map, is essentially an interactive site that turned the Google map into a "global scrapbook" where queer people can share their experiences, leaving comments on cities around the world that have given them a personal moment (coming out stories and awareness stories, etc.). Of course, although these efforts are good steps towards creating fully accepting societies, the more practical changes in public spaces are still urgent.

Image Source: informationisbeautifulawards.com

According to the research "Queering Public Space" made by the University of Westminster, there are three basic conditions in the design of spaces, which will be able to offer safety to the people of the queer community. The primary issue is that of privacy in public spaces. This can be achieved by creating parks, where the green spaces will be placed in such a way as to ensure the feeling of privacy of individuals. In addition, the existence of adequate lighting has a positive effect, since it minimizes the feeling of fear and isolation. The above, as well as rejecting large open parks or, on the other end, claustrophobic spaces, were the main points in the answers of the survey respondents.

This more diligent design approach was followed in Vienna, where designers preferred to install warm street lighting in order to reduce violent incidents. Also, the city's parks were designed in a rather complex way, through the redevelopment of areas for semi-private use. This alternation of visible-invisible seems to have offered individuals a considerable amount of private space, within an eminently public park.

Also, on a secondary level, urban planners must consider the necessity of designing housing for all family types. Design focuses predominantly on heterosexual individuals of all age groups and their daily lives. An example of why this is problematic is the older members of the queer community and the difficulties they face in the field of care and housing. A possible solution to this concern is the creation of nursing homes exclusively for community members, aiming at their best care, away from the negative and often homophobic comments of their peers. Of course, the staff should have the corresponding training, to avoid behaviours from which the members need to be protected. However, the difficulties faced by queer people are unfortunately not limited to nursing homes. The situation described above is just an example of the more general tendency of modernist architecture, which revolves around a binary perception of planning and design, which is evident everywhere.

The project Stalled! by transgender historian Susan Stryker, architect Joel Sanders and professor Terry Kogan is on the same wavelength. Concerning the configuration of public washrooms, this project is theoretically based on the work of Lucas Cassidy Crawford, “Transgender Architectonics: The Shape of Change in Modernist Space” (2015). Essentially, the visionaries of Stalled! promise to create a kind of space for everyone, free from unnecessary divisions, serving people of different genders, PWDs, etc.

The visibility of the community’s timelessness

In addition to urban planning, the third part of the research and the main point of the whole effort of inclusion focuses on the representation of the life of LGBTQ+ citizens over time. This can be achieved by placing and creating monuments or memorial sites, which will act as symbols of the continuous active life of the individuals. The aim of this effort is to raise awareness and strengthen the community's visibility in society. The thought "we are everywhere" strengthens physical and spatial presence, removing queer people from their previous social obscurity.

The Memorial to the Homosexuals Persecuted under Nazism, Berlin | Image Source: nbcnews.com

Such actions have begun to take place in various European countries. The Memorial to the Homosexuals Persecuted under Nazism in Berlin's Tiergarten, a work by artists Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, was created in 2008. The cube-shaped structure is made of concrete, having an opening at the front inside which the visitor can see two men kissing. This secret act functions as a symbol of the situation in which LGBTQ+ members lived, afraid to express themselves publicly. Similar monuments exist in Frankfurt (Frankfurter Engel, 1994) and Cologne (Kölner Rosa Winkel, 1994), as a reminder of the atrocities the community suffered during the Nazi period.

Similar monuments exist in many countries of the world. Some examples are the Gay Liberation Monument (New York), the Alan Turing Memorial (Manchester) or the highly minimalistic Monumento en memoria de los gais, lesbianas y personas transexuales represaliadas in Barcelona. Similar actions have taken place in France, with the decision to name streets, parks, etc. in honour of well-known LGBTQ personalities, such as Marie Thérèse-Auffray, Coccinelle or the couple Jean Diot and Bruno Lenoir.

Monumento en memoria de los gais lesbianas y personas transexuales represaliadas, Barcelona | Image Source: es.m.wikipedia.org

This interactive approach of acceptance through the presence of monuments can obviously trigger a new beginning for the free life of the queer community. However, although organized efforts are increasing, there does not seem to be any centrally organized strategy to reduce homophobic crimes or to finance the regeneration of areas where most incidents of homophobic violence are found. Is it time, then, for society to see the problem as a whole and implement the various sociological and urban studies, looking towards the future, free from any prejudice of the past?

Further reading/ Sources

Olivier Vallerand, Queer Looks On Architecture: From Challenging Identity-Based Approaches To Spatial Thinking. from: https://www.archdaily.com/963534/queer-looks-on-architecture-from-challenging-identity-based-approaches-to-spatial-thinking.

Ghaziani A. (2020). Why Gayborhoods Matter: The Street Empirics of Urban Sexualities. The Life and Afterlife of Gay Neighborhoods: Renaissance and Resurgence, 87–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66073-4_4.

Evan Pavka, What Do We Mean By Queer Space?. from: https://www.azuremagazine.com/article/what-do-we-mean-by-queer-space/.

Pippa Catterall & Ammar Azzouz, The queer city: how to design more inclusive public space. from: https://theconversation.com/the-queer-city-how-to-design-more-inclusive-public-space-161088 .

How to be an LGBT-Inclusive Nursing Home. from: https://www.storiicare.com/blog/lgbt-inclusive-nursing-home.

Katie Cashman & Waldo Soto. Cultivating Urban Queer Inclusivity in Berlin, Nairobi, and Santiago. from: https://www.urbanet.info/queer-cities-berlin-nairobi-and-santiago/.

Katherine Guimapang. Perceptions of Safety: Weronika Zdziarska Questions Urban Design and Its Impact on Gender-Based Violence Experienced by Women in Cities. from: https://archinect.com/features/article/150281725/perceptions-of-safety-weronika-zdziarska-questions-urban-design-and-its-impact-on-gender-based-violence-experienced-by-women-in-cities?fbclid=IwAR2aImahxvf8GlAlJYAHn5roybke7QHB5yZanWIfklxFll9trQW1Ppbry1U.

More about Stalled! project: https://www.stalled.online/.

Info about Gayborhoods: https://gayborhoodfoundation.com/.

Info for Queering the Map: https://www.queeringthemap.com/ and Lucas Larochelle’s i-D interview: https://i-d.vice.com/en_uk/article/vbxkpb/queering-the-map-is-connecting-queer-moments-in-life.