Από τα Cyborgs της Donna Haraway στην ψηφιακή αρχιτεκτονική και τέχνη.

DS.WRITER:

Sophia Throuvala

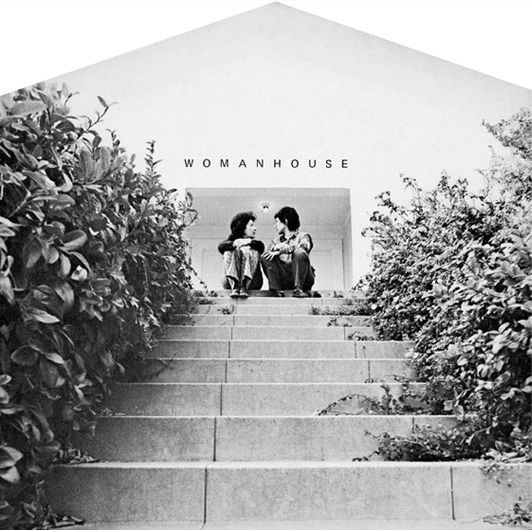

Κεντρική Εικόνα: Woman's House, 1972 | Πηγή εικόνας: moma.org

Το πρώτο κύμα φεμινισμού έφερε το ζήτημα της ορατότητας στο προσκήνιο, με στόχο την αποκατάσταση της γυναικείας παρουσίας σε μια ιστορία ανδροκρατούμενη σε όλους τους τομείς, από την κοινωνική ζωή και τα δικαιώματα, την πολιτισμική παραγωγή και την προσβασιμότητα, μέχρι τον ακτιβισμό και την πολιτική. Μέσα στις διεκδικήσεις αυτές ξεκινάει μια συζήτηση για τον αρχιτεκτονικά δομημένο χώρο, ο οποίος, εξαιτίας της ανισότητας στον τομέα παραγωγής, παραμένει ανδροκρατούμενος και ανδροαναφορικός, ενώ ο τρόπος σύλληψης και υλοποίησης αρχιτεκτονικών πρότζεκτ παραμένει θα λέγαμε ηδονοβλεπτικός και υποτιμητικός ως προς τη γυναίκα.

Οι χώροι στέγασης και εργασίας παρατηρείται πως κατά ένα 98% είναι υλοποιημένοι και σχεδιασμένοι από άνδρες, και εξυπηρετούν -σκόπιμα ή μη- έναν άνισο σχεδιασμό, έναν δεσμευτικό χώρο για τις γυναίκες, τις οποίες μοιάζει να “εξυπηρετεί” μέσω αναπαραγωγής στερεοτύπων (man made environment). Στο πλαίσιο αυτό η Dolores Hayden αναρωτιέται, πώς άραγε θα ήταν μια μη-σεξιστική πόλη, υπονοώντας πως αν οι γυναίκες είχαν τη δυνατότητα να χτίσουν και να σχεδιάσουν έναν κόσμο από τη δική τους οπτική, βάσει αναγκών και όχι συμφερόντων, πιθανότατα ολόκληρη η έννοια και η μορφή της πόλης θα ανατρέπονταν, και μαζί τους η παράδοση, ο πολιτισμός, η φιλοσοφία και φυσικά η ψυχανάλυση.

Οι τόσο αδρές διαχωριστικές γραμμές μεταξύ (των δύο μόνο) φύλων οδήγησαν στο δεύτερο κύμα, το οποίο, σε μια πιο μεταδομιστική λογική, προτείνει την επανοικειοποίηση του χώρου μέσω της μεταβολής τους ριζοσπαστικά. Αγκαλιάζει ιδεολογικά την ανάγκη προβολής της αναχαίτισης των σχέσεων εξουσίας και των διαχωρισμών με βάση το φύλο, όπως προκύπτουν από τη μελέτη της αρχιτεκτονικής. Η αρχιτεκτονική θα μπορούσε στα πλαίσια αυτά να ασκήσει κριτική και να τεκμηριώσει κατά κάποιον τρόπο την ανισότητα, δεδομένου πως το ζήτημα της “φύσης” ενυπάρχει εξ αρχής στη φιλοσοφία του χτίζειν, δημιουργώντας έτσι μια σχετική παράδοση, από την οποία δεν μπόρεσαν να ξεφύγουν ακόμα και οι ελάχιστες γυναίκες σχεδιάστριες. Σε τι αναφερόμαστε άλλωστε όταν μιλάμε για “λειτουργικούς χώρους”;

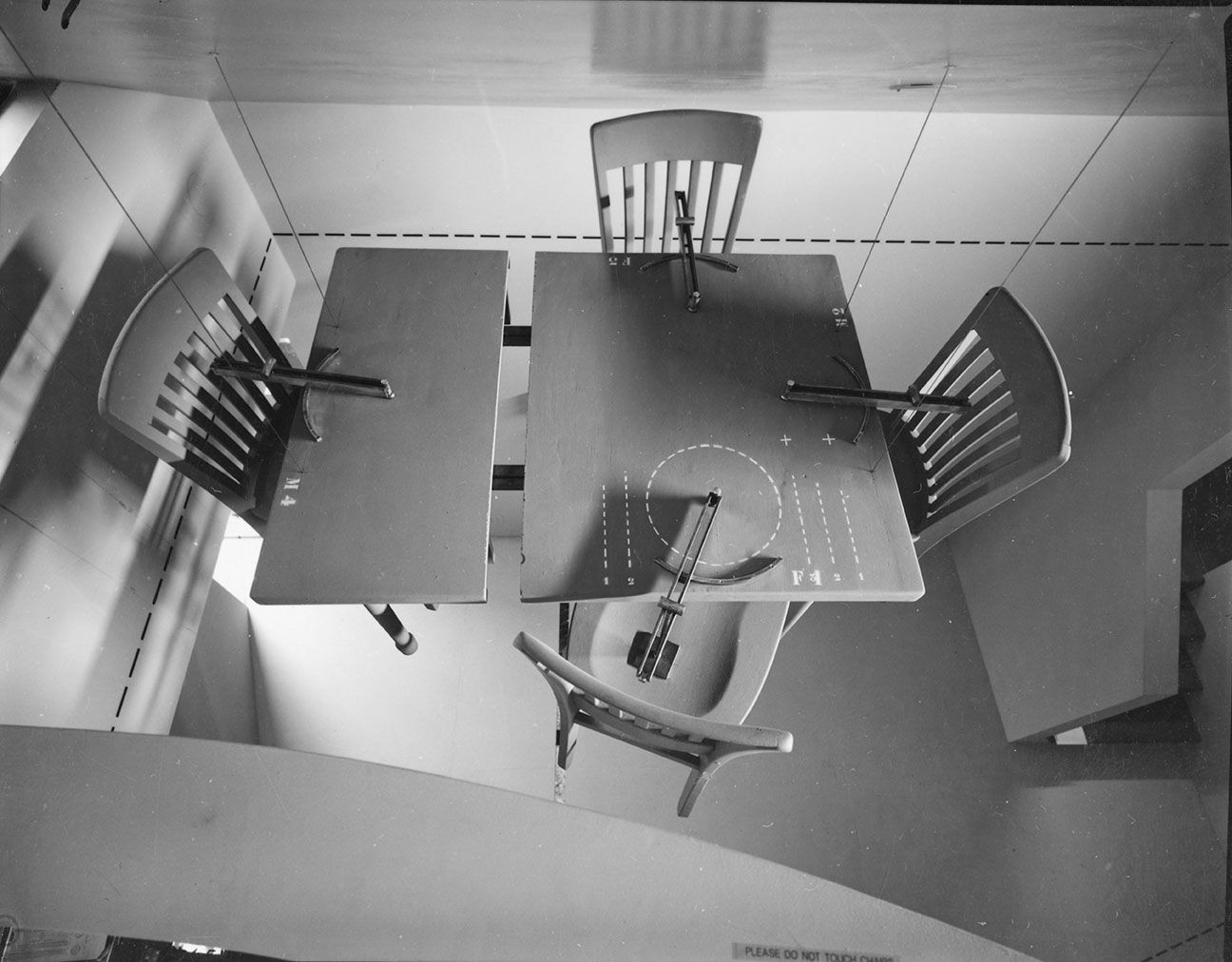

Ωστόσο, παρά τις συζητήσεις και την κινητοποίηση φεμινιστριών (όπως οι Mary Mcleod, Catherine Ingraham, An Bergrein κα), και με εξαίρεση τα καινοτόμα και ευρηματικά έργα και εγκαταστάσεις -όπως το εμβληματικό WomenHouse του 1972 των Judy Chicago και Miriam Schapiro ή τα TranSit & SoftCell των Diller+Scofidio, και κυρίως το withDrawing Room του 1987, το οποίο μπορεί να αναλυθεί σε μικρά, μεταβλητά και εφήμερα δομικά στοιχεία στο εσωτερικό ενός δωματίου, τα οποία εξυπηρετούν και διασφαλίζουν μια παρουσία-απουσία που εγγράφει άμεσα τις ιδέες της Donna Haraway (Cyborg Manifesto ‘85) και της Julia Kristeva (powers of horror, ‘80)-, το υλικό και η σκέψη στην αρχιτεκτονική δόμηση δεν άλλαξαν εν τοις πράγμασι. Οι ιδέες δεν έγιναν πράξη ή ριζική μετατόπιση από τη φιλοσοφία στον σχεδιασμό και την υλοποίηση.

The withdrawing Room Elizabeth Diller, Ricardo Scofidio 1987, Photography by Ben Blackwell, Courtesy of Diller Scofidio + Renfro

Παρά την ακαδημαϊκή παρουσία φεμινιστριών τις δεκαετίες του ‘80 και του ‘90, δεν ήταν μόνο η αρχιτεκτονική που δεν άλλαξε ριζικά αλλά και η μη συμπερίληψη των queer ατόμων στις θεωρίες αυτές. Στους πάνω από 30 τόμους, βιβλία και σχετικές με το φύλο ανθολογίες, δεν υπάρχει χώρος για το “queer space movement”. Εξαίρεση αποτελεί το A Cyborg Manifesto της Donna Haraway, η οποία, με τη φράση “in short, we are all cyborgs”, οραματίζεται το μέλλον του φεμινισμού και κάνει εμμέσως λόγο για τα προβλήματα που επιφέρει τελικά ο διαχωρισμός σε δυο, και μόνο, βασικά φύλα. Σε συνδυασμό με τις ψυχαναλυτικές θεωρίες της Julia Kristeva για το σώμα ως ως μη απαραίτητο καθεαυτό, δημιουργείται ένα ιδεολογικό corpus που διευρύνει τη συζήτηση, τόσο από την αρχιτεκτονική στον κυβερνο-χώρο, όσο και από το σώμα στο μηχάνημα, από το υλικό στη διαφάνεια και από τη δυϊστική θεωρία των φύλων στη ρευστότερη δυνατή μορφή τους.

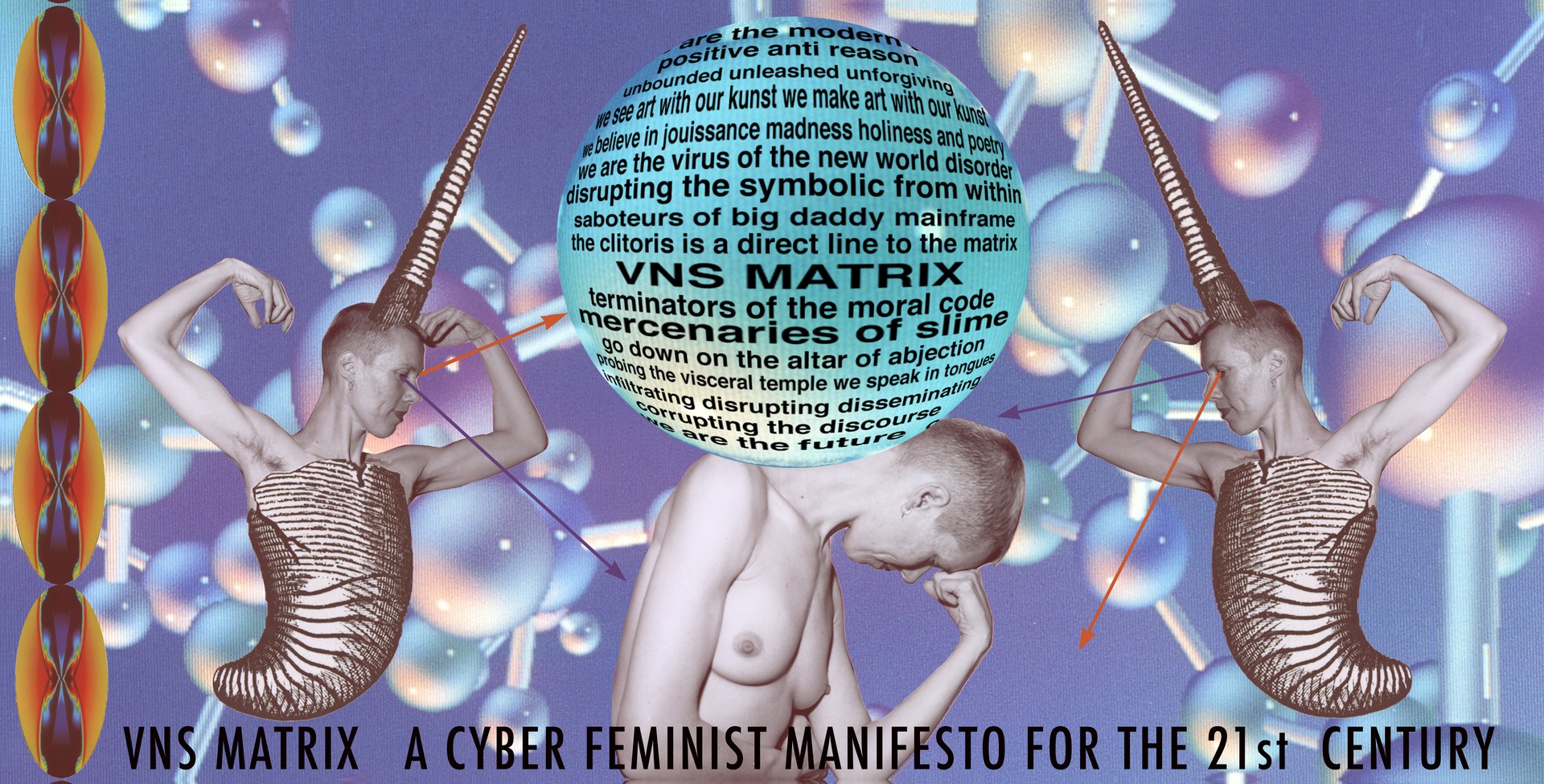

Παράλληλα με τη διάδοση του world-wide-web στην αρχή των 90ς, και σε συνδυασμό με τις παραπάνω θεωρήσεις, εμφανίζεται ο Κυβερνοφεμινισμός στην τέχνη και την κριτική, θεωρώντας τον κυβερνοχώρο ως ένα ακόμα “μέρος” δημιουργημένο από τους άνδρες για την εξυπηρέτηση των ίδιων (computer made by men for men). Οι VNS Matrix (1993), κολεκτίβα γυναικών από τη Νότια Αυστραλία, αρχίζουν να επεξεργάζονται έννοιες που αφορούν τον κυβερνοχώρο και θέτουν το σημαντικό ερώτημα: Could we use technology to hack the codes of patriarchy? Could we escape gender online? Μπορεί άραγε ένας νέος χώρος στον οποίο έχουν μεταφερθεί όλα τα “επίγεια” προβλήματα, όπως ο σεξισμός, οι διακρίσεις, η τρανσφοβία, η ομοφοβία και οι φυλετικές περιθωριοποιήσεις, να νικηθεί και να εκδημοκρατιστεί;

VNS Matrix 1991 A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century | Πηγή εικόνας: monoskop.org

Στα επόμενα χρόνια, κύριο “όχημα” των queer και feminists εικαστικών και σχεδιαστών (και γενικότερα των δημιουργικών θηλυκοτήτων) έγινε η digital art και το digital design and fabrication, μέχρι και τα πλέον διαδεδομένα nfts. Παρατηρείται σημαντική αύξηση στην παραγωγή 3d-printed κεραμικών και υφασμάτων, και γενικότερα μια τάση στο εργόχειρο και στην αναπροσαρμογή οικιακής εργασίας ως new media design. Πρόκειται για μια επανοικειοποίηση και επαναξιολόγηση του παραδοσιακού, των ιστορικών μεθόδων παραγωγής αντικειμένων, που έχουν άμεση σχέση με το πώς η γυναίκα στην ιστορία περνάει τον χρόνο στο σπίτι της και δημιουργεί χώρο μέσα στον χώρο, διακοσμώντας, αποθηκεύοντας και ταξινομώντας τον χώρο που ζει σε μικρο-περιοχές, η κάθε μια με δική της σημειολογία και συμβολισμούς. Μπορούμε ακόμα να εντοπίσουμε πολύ ζωντανή την παρουσία τής Haraway μέσα σε αυτόν τον νέο τύπο συνέχισης της παράδοσης, στο σημείο που η “παραγωγός” αποτελεί οργανικό μέρος του φυσικού χώρου.

Σύμφωνα με την Donna Haraway, ένα cyborg είναι κάτι το μεταιχμιακό, ένας οργανισμός και μια μηχανή, δηλαδή αποτελεί οργανικό μέρος μιας κοινωνίας. Η πολιτιστική κληρονομιά, πέραν της αρχιτεκτονικής, με εστίαση στο domestic και στο “λαϊκό”, θα λέγαμε πως δημιουργήθηκε ιστορικά και ουσιαστικά από γυναίκες, με τη χρήση και αξιοποίηση της εκάστοτε τεχνολογίας ακριβώς τη στιγμή που αυτή γινόταν προσβάσιμη, με στόχο την παραγωγή αγαθών εικαστικών και χρηστικών, όπως τα χαλιά, η κεραμική, τα υφαντά, τα κεντήματα, τα καλάθια κα. Αντικείμενα δηλαδή που είναι σήμερα απολύτως συνδεδεμένα με το design.

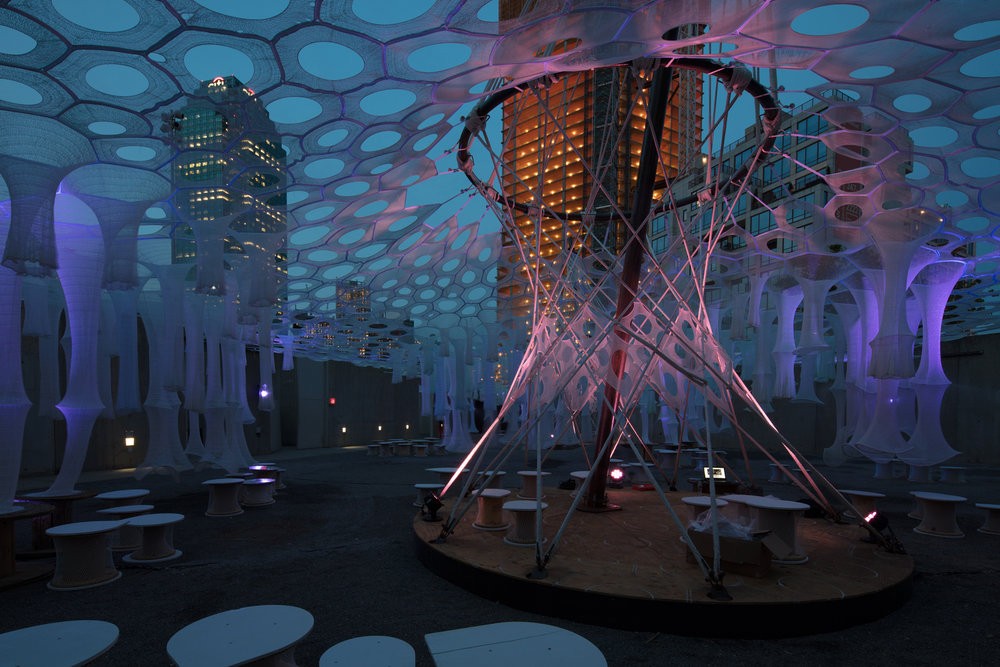

Silkworm-spun pavilion, Neri Oxman | Πηγή εικόνας: oxman.com

Έργα, digital design και fabrication, δεν δημιουργούνται αποκλειστικά από γυναίκες. Ο διαχωρισμός των φύλων δεν υφίσταται στην επαυξημένη εποχή, αν και κάποια από τα πιο σημαντικά δείγματα, όπως τα “Silk Pavilion” της Neri Oxman και “Lumen” της Jenny Sabin, έχουν γίνει από γυναίκες. Στις δυο αυτές περιπτώσεις μάλιστα, το “λαϊκό” και παραδοσιακό αποκτά διαστάσεις αρχιτεκτονικής, κάνοντας το μέσα έξω με έναν τρόπο που ποτέ πριν δεν εφαρμόστηκε στη δόμηση. Το φύλο, εδώ, ενυπάρχει στις δημιουργίες ως “φόρος τιμής”. Το φύλο ανιχνεύεται μέσα στις μεθόδους που αξιοποιούνται με νέα μέσα, ως αναφορά στην κληρονομιά της οικιακής εργασίας, με έναν τρόπο μεγαλειώδη, μνημειακό και σύγχρονο που οραματίζεται φουτουριστικές πολιτείες μέσα από ένα βαθιά φεμινιστικό πρίσμα.

Πηγή εικόνας: jennysabin.com

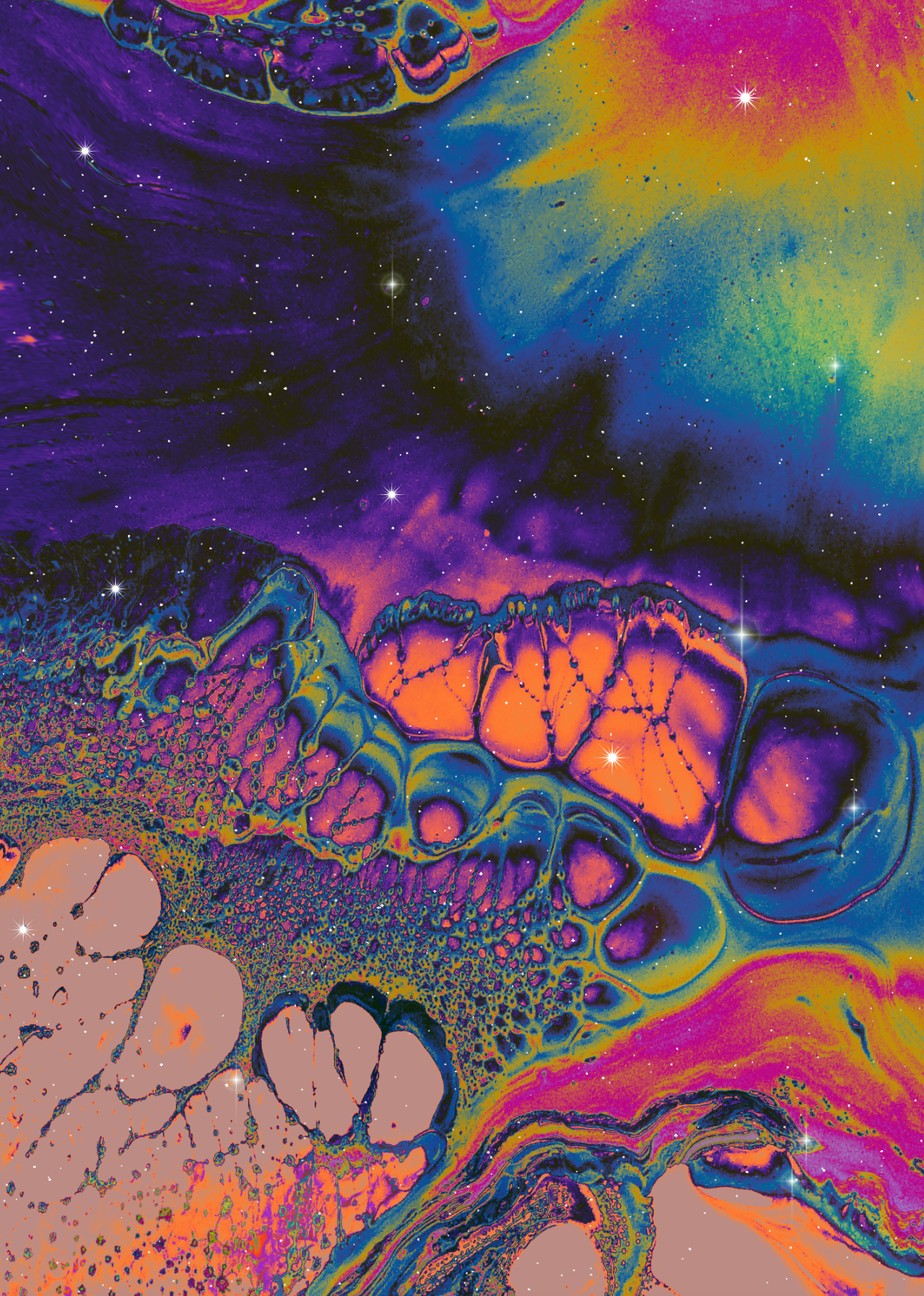

Το fabrication και η αρχιτεκτονική συναντώνται στον χώρο των πλέον διαδεδομένων NFTs με έναν εντελώς καινούριο τρόπο, ενώ οι διαχωρισμοί με βάση το φύλο παραμένουν υπαρκτοί. Πρόσφατα, η Alycia Rainaud, η οποία είναι graphic designer, δημιουργεί μερικά από τα πιο ακριβοπληρωμένα nfts και δήλωσε πως, ακόμα και στη συνθήκη των nfts, που δεν έχει θα λέγαμε προηγούμενο -όπως άλλες μορφές τέχνης-, δεν είναι μυστικό πως οι άνδρες ευνοούνται και πάλι σε σχέση με τις θηλυκότητες, οι οποίες σύμφωνα με τελευταίες μελέτες αποτελούν μόλις το 15% των crypto-users.

Tied Up to the Past, «Maalavidaa» courtesy of «Maalavidaa» | Πηγή Εικόνας: vogue.com

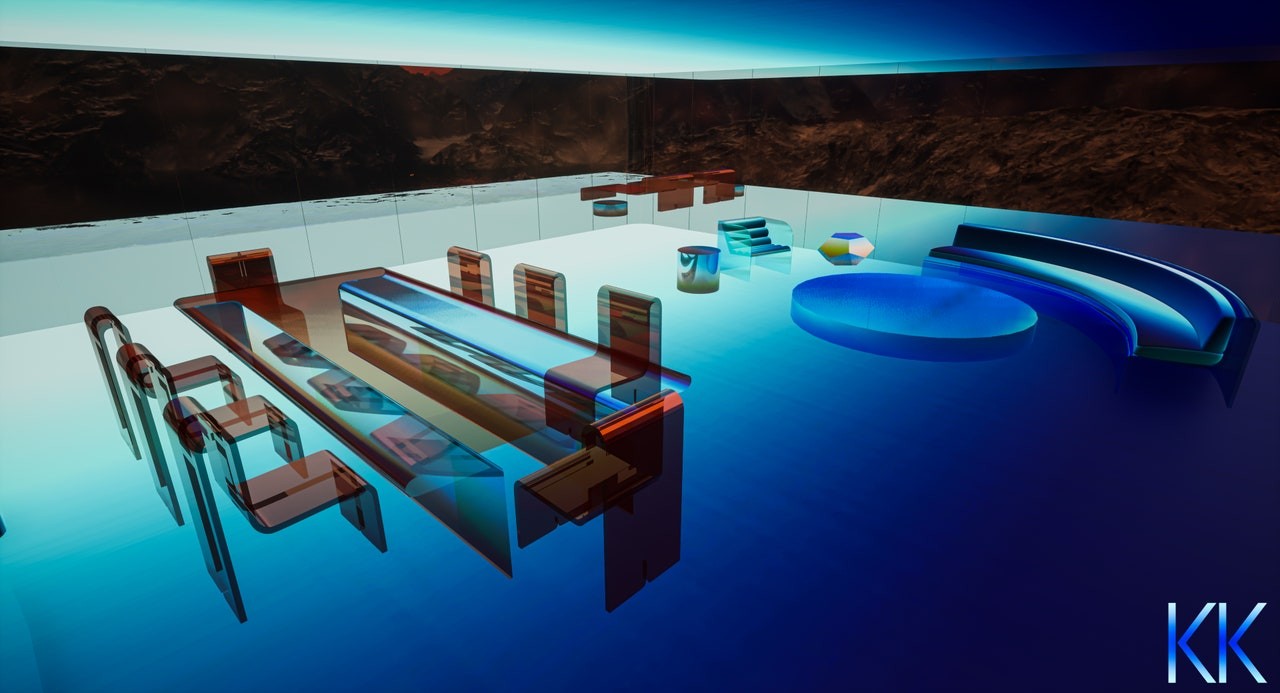

Τέλος, η Krista Kim, η πρώτη δημιουργός “αρχιτεκτονικού” nft, δημιουργός του Mars House, ενός σπιτιού εμπνευσμένου από μια εξ ολοκλήρου νέα θεώρηση της αρχιτεκτονικής, θεωρεί πως τα nft είναι εδώ για να μας διδάξουν την εξέλιξη του design όπως δεν μας τη δίδαξε κανείς προηγουμένως. Όπως δηλώνει: “Σύντομα, θα στολίσουμε τη ζωή μας με τέτοια τέχνη, ποίηση, μόδα, μουσική. Με συλλεκτικά αντικείμενα και διαδραστικές εμπειρίες, χρησιμοποιώντας αποκλειστικά AR τεχνολογία.”

Ακόμα δεν είναι σαφές κατά πόσο μιλάμε με όρους πραγματικότητας, ουτοπίας ή δυστοπίας, ωστόσο μπορούμε να πούμε πως η Haraway προέβλεψε και ίσως καθοδήγησε, ως έμπνευση, ένα μέρος αυτού που συμβαίνει σήμερα στον χώρο του design, της τέχνης και της αρχιτεκτονικής. Βρισκόμαστε ακόμα στο μεταίχμιο φύσης και τεχνολογίας, ή τείνουμε να αφήνουμε πια σημαντικότερο ψηφιακό αποτύπωμα απ’ ότι “υλικό”, κάνοντας έτσι τα όρια μεταξύ των διπόλων σώμα - μη-σώμα, παρουσία - απουσία ακόμα πιο δυσδιάκριτα;

Krista Kim’s Mars Housecourtesy Krista Kim | Πηγή εικόνας: vogue.com

Hayden, Dolores (1980). What Would a Non-Sexist City Be Like? Speculations on Housing, Urban Design, and Human Work. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 5(S3)

Shelby Doyle & Leslie Forehand, “Fabricating Architecture: Digital Craft as Feminist Practice,” in the Avery Review 25 (September 2017),

DORA EPSTEIN JONES, Extreme Makeover; or, How the F-word Shaped Contemporary Architecture Southern California Institute of Architecture

ΠΗΓΕΣ:

.jpg)

.jpg)