Παιδικές χαρές: Από τον Van Eyck στον Πικιώνη

DS.WRITER:

Tasos Giannakopoulos

Κεντρική Εικόνα: Aldo van Eyck, Amsterdam | rocagallery.com

“Η δομή του παιχνιδιού απορροφά αυτόν που παίζει μέσα του, και τον ελευθερώνει από το βάρος της πρωτοβουλίας, που αποτελεί την πραγματική κόπωση της ύπαρξης.”

Hans Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method

Το παιχνίδι αποτελεί ξεχωριστή οντολογική κατάσταση. Όταν παίζουμε, κάνουμε κάτι που, για όσο διαρκεί, αναστέλλει το βάρος της ύπαρξής μας. Είναι μια πλήρως ανάλαφρη κατάσταση, χωρίς πρακτικό αποτέλεσμα με απόλυτες συνέπειες, ενώ ταυτόχρονα απαιτεί από τους παίκτες να το πάρουν απολύτως σοβαρά και να υποταχθούν στους κανόνες και στα φυσικά, γεωμετρικά του όρια, που μπορεί να εκτείνονται από τη μικρή ξύλινη επιφάνεια λίγων εκατοστών ενός ταμπλό για τάβλι, μέχρι το μέγεθος ενός ποδοσφαιρικού γηπέδου. Τα παιδιά είναι πιο τυχερά από εμάς τους ενήλικες στο συγκεκριμένο πεδίο. Τους έχει δοθεί συγκεκριμένος χώρος μέσα στην ίδια την πόλη, για να εξασκούν αυτό τους το δικαίωμα. Αυτοί οι χώροι ονομάζονται παιδικές χαρές, είναι μια τυπολογία του τελευταίου αιώνα, μιας και τα παιδιά μέχρι πρόσφατα δεν αναγνωρίζονταν ως ξεχωριστές οντότητες από τις κοινωνίες, και είναι αφιερωμένοι στο παιχνίδι και σε όλες τις υπόλοιπες διαστάσεις που φέρνει μαζί του.

Aldo van Eyck, Playground, Amsterdam | rocagallery.com

Aldo van Eyck, Amsterdam | hertzberger.nl

Οι πιο όμορφες παιδικές χαρές που έχω συναντήσει ποτέ μου, έχουν σχεδιαστεί από τον Ολλανδό αρχιτέκτονα Aldo van Eyck και είναι οι θρυλικές παιδικές χαρές του Άμστερνταμ. Κατασκευάστηκαν εκατοντάδες μετά τον δεύτερο Παγκόσμιο Πόλεμο από τη δημόσια υπηρεσία της πόλης, ως μια στρατηγική αναζωογόνησης και επανακατάληψης από τους πολίτες των κατεστραμμένων, βομβαρδισμένων οικοπέδων της. Ήταν μια πρωτοβουλία που αρχικά τοποθετούσε και τα παιδιά ως μέρος της ανοικοδόμησης και επανασύστασης του αστικού ιστού της πόλης, και προωθούσε τη συναναστροφή και την επαναδιατύπωση των κοινωνικών σχέσεων μέσα στον φυσικό της χώρο. Οι γεωμετρικές κατασκευές του Van Eyck δεν ήταν συγκεκριμένα παιχνίδια που απαιτούσαν συγκεκριμένο παιχνίδι, αλλά πλαστικά γεγονότα στον χώρο, που καλούσαν -με τους ενδιάμεσους χώρους που δημιουργούσαν και τις μορφές που συνέτασσαν- την ελεύθερη ανακάλυψη των φανταστικών πιθανοτήτων του χώρου. Αντί για την ενασχόληση των παιδιών με αγγλικά, γερμανικά, κολυμβητήριο, πιάνο και μπαλέτο, οι παιδικές χαρές του Ολλανδού αρχιτέκτονα εξυπηρετούσαν λιγότερο κανονισμένες και κανονιστικές δραστηριότητες, που είχαν στόχο να αναπτύξουν διαφορετικούς τομείς των δεξιοτήτων τους, όπως είναι η φαντασία, η ευελιξία και η κοινωνικότητα.

Assemble Studio, London | assemblestudio.co.uk

Αντίστοιχη κατεύθυνση έχουν και οι Assemble studio, με τους χώρους και τις εγκαταστάσεις που δημιουργούν για παιδιά. Είναι μια αρκετά παράδοξη για την εποχή κατεύθυνση, που ενθαρρύνει το παιχνίδι χωρίς επίβλεψη από ενηλίκους και με έμφαση στη σωματική δραστηριότητα. Η κολεκτίβα των Assemble είναι πολύ πιθανό να έχει επηρεαστεί από τις λεγόμενες “junk playgrounds” του Δανού αρχιτέκτονα τοπίου Carl Theodor Sorensen, που, βασιζόμενοι στις ιδέες του Friedrich Froebel για το φυσικό παιχνίδι, δημιουργούν τοπία από ξεσκαρταρισμένα αντικείμενα, όπως αυτοκίνητα, στύλους, χαρτοκούτια και ό,τι άλλο μπορεί να απορριφθεί, και σε ένα προστατευμένο από ψηλή πρασινάδα πεδίο τα παιδιά αφήνονται να παίξουν, να φανταστούν και να συνεργαστούν.

Assemble Studio, Glasgow | assemblestudio.co.uk

Carl Theodor Sorensen, Copenhagen | artblart.com

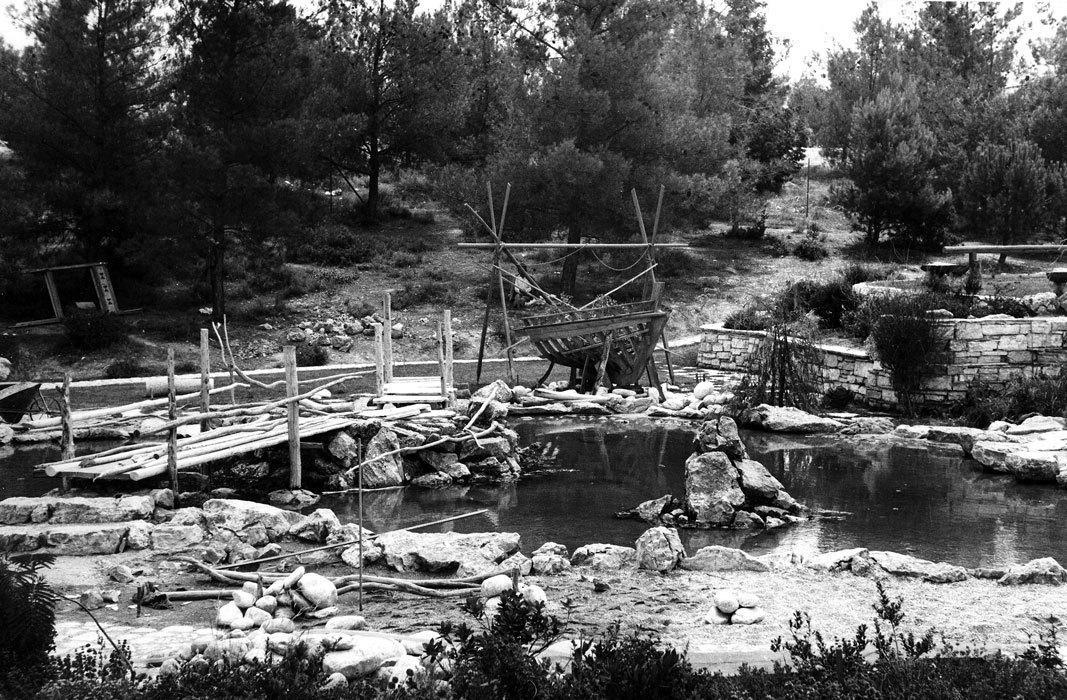

Σε μια πιο αρχιτεκτονική διατύπωση κινείται ο Δημήτρης Πικιώνης στην Ελλάδα, σχεδιάζοντας την περίφημη παιδική χαρά στη Φιλοθέη. Θραύσματα ανοικτά στη σωματική και διανοητική δημιουργικότητα των παιδιών τοποθετούνται στον χώρο, για εκμετάλλευση από τα παιδιά. Μια βάρκα που έχει ξεβραστεί στη στεριά, πέτρες προσεκτικά τοποθετημένες, στύλοι και αρχετυπικές καλύβες ενός πνευματικού τόπου ολοκληρώνουν την οργανική σύνθεση στον χώρο. Σύμβολα πάνω στα δομικά μέλη των εμπνευσμένων από την ιαπωνική αρχιτεκτονική μερών του έργου, δημιουργούν ελεύθερες συσχετίσεις και θεωρήσεις σχετικά με -και πέρα από- τον υφιστάμενο χώρο. Ο ονειρικός τόπος ενός από τα τελευταία έργα του Έλληνα αρχιτέκτονα παραθέτει και υπερθέτει στοιχεία από Δύση και Ανατολή, σε διάλογο και έντονο παιχνίδι αναμεταξύ τους, των ίδιων των μέσων της αρχιτεκτονικής δημιουργίας αυτή τη φορά.

Dimitris Pikionis, Athens | doma.archi

Dimitris Pikionis, Athens | doma.archi

Σε έναν κόσμο που οι δημόσιοι χώροι συμπυκνώνονται συνέχεια, οι παιδικές χαρές κάτι υπενθυμίζουν. Σε κοινωνίες όπου η κατανάλωση πάσης μορφής ενέργειας με στόχο κάποιο απώτερο παραγωγικό διακύβευμα είναι το πρότυπο, το ελεύθερο παιχνίδι σπανίζει. Κατασκευάζουν την εκτέλεση ενός ενδιαφέροντος τίποτα με μοναδικό σκοπό την αγνή παιδική απόλαυση. Εξάλλου, και για να γυρίσουμε κυκλικά στον Van Eyck σαν σε γύρω-γύρω όλοι, μια πόλη που δεν έχει χώρο για το παιδί, είναι ένα διαβολικό πράγμα.