Η Mona Hatoum στο Βερολίνο και το ευαίσθητο σώμα του έργου της

DS.WRITER:

Tasos Giannakopoulos

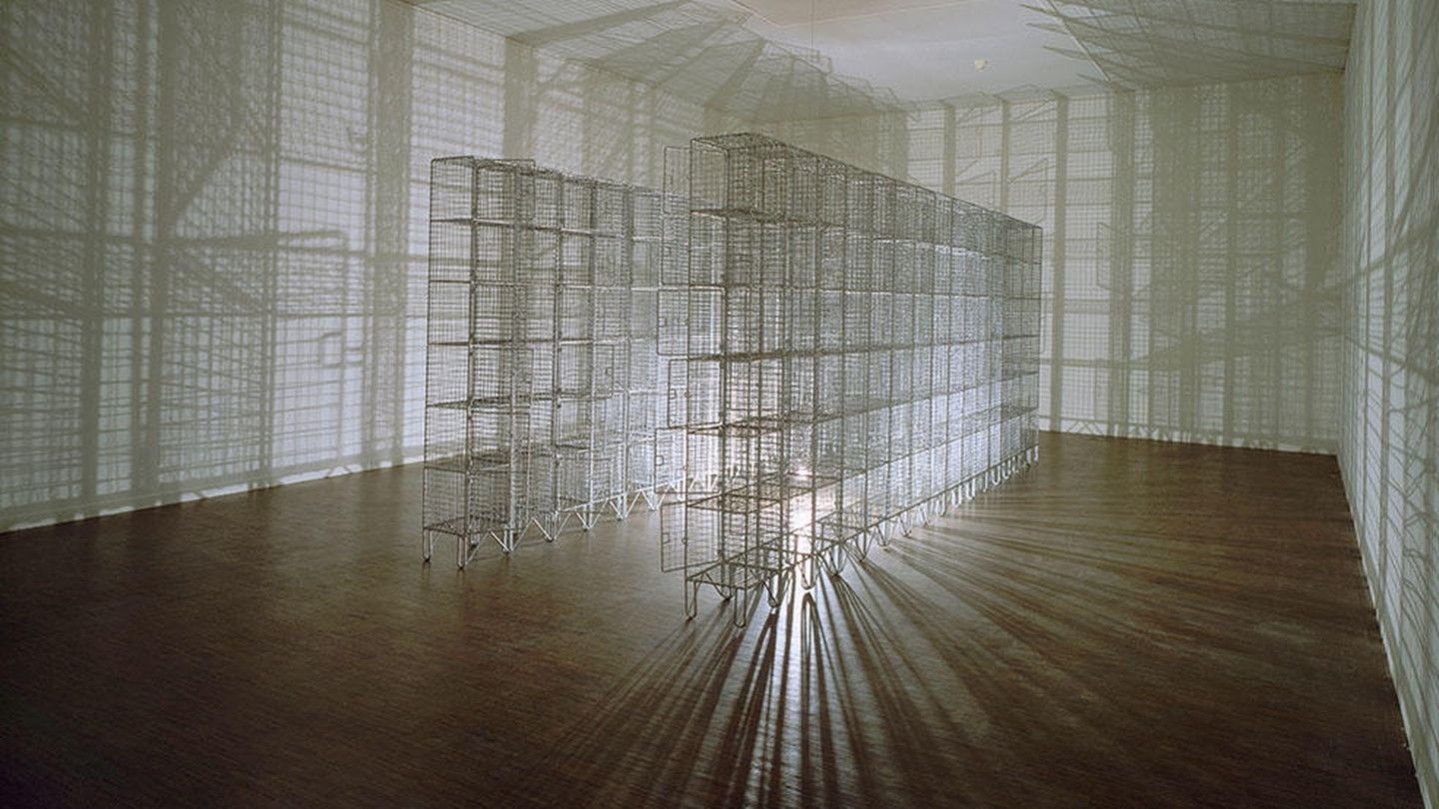

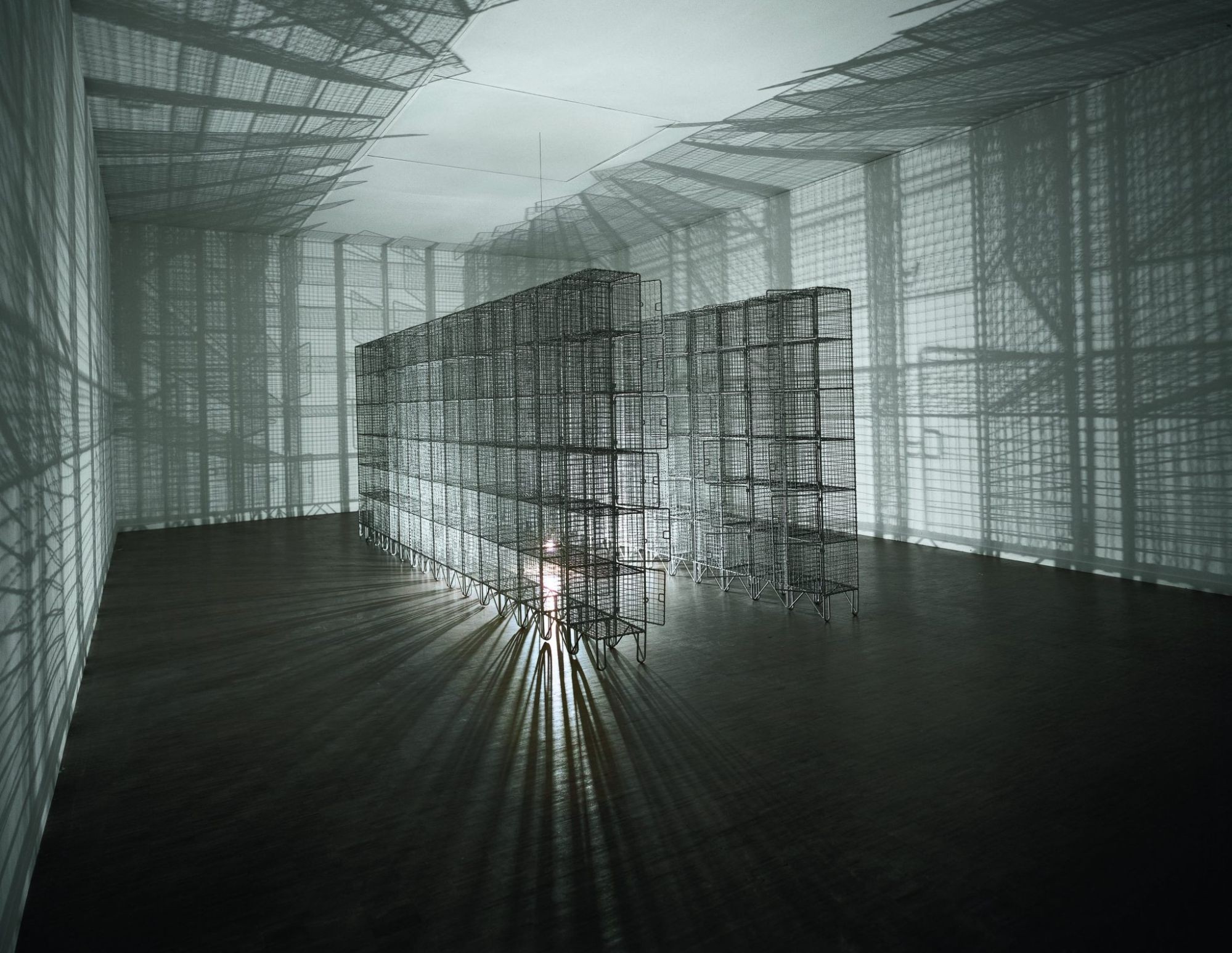

Κεντρική Εικόνα: Light Sentence | jungle-magazine.co.uk

Ευκαιρία να μιλήσουμε για τη Mona Hatoum. Το Georg Kolbe Museum, το Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, το Georg Kolbe Museum και το KINDL – Centre for Contemporary Art, όλα με βάση το Βερολίνο, έχουν εκθέσεις και εγκαταστάσεις με το έργο της. Το πρώτο ινστιτούτο, μέσα από τα έργα της Hatoum που, φυσικά, το επιτρέπουν γενναιόδωρα, εξερευνά ιδέες γύρω από το σπίτι, τη δομική βία και άλλα ανθρωπιστικά θέματα. Το δεύτερο ινστιτούτο παρουσιάζει μια σειρά από γλυπτικές εγκαταστάσεις, μεταξύ των οποίων και το υπέροχο Remains of the Day (2016-18), καθώς και νέα έργα συγκεκριμένα για τον χώρο. Αυτήν την κατεύθυνση της εγκατάστασης για συγκεκριμένο χώρο (site-specific installation) έρχεται να εκμεταλλευτεί πλήρως το KINDL, στο παλιό εργοστάσιο ζυθοποιίας και συγκεκριμένα στον πύργο που συνήθιζε να γίνεται ο βρασμός της μπύρας, όπου πολύ εύστοχα βλέπουμε την επεξεργασία ζητημάτων από την τωρινή κοινωνική μας πραγματικότητα, που αντίστοιχα βρίσκεται σε σημείο βρασμού και αναταραχών.

Mona Hatoum | wikimedia.org

H Mona Hatoum είναι γεννημένη το 1952 στη Βηρυτό του Λιβάνου από Παλαιστίνιους γονείς. Όπως αναφέρει η ίδια, η οικογένειά της αποτελεί μέρος εκείνων των Παλαιστινίων που έγιναν εξόριστοι στον Λίβανο το 1948 και δεν τους δόθηκε η Λιβανέζικη υπηκοότητα προκειμένου να αποθαρρυνθεί η ενσωμάτωσή τους. (BOMB Magazine with Janine Antoni, 1998)

Προφανώς, τα ζητήματα της καταγωγής της είναι εμφανή στη δουλειά της, αλλά όπως όλοι οι καλοί τα ξεπερνά και χτίζει κάτι μεγαλύτερο μέσα από αυτά. Όσον αφορά το υπόλοιπο υπόβαθρό της, η ίδια σπουδάζει γραφιστική στο Πανεπιστήμιο της Βηρυτού και, αργότερα, εκπαιδεύεται στην Byam Shaw School of Art και στο Slade School of Fine Art στο Λονδίνο, όπου και διαμένει πλέον, ύστερα από τα γεγονότα του Λιβανέζικου εμφυλίου το 1975. Κάποιον καιρό δούλεψε και στον χώρο της διαφήμισης, που, εν τέλει, δεν την κράτησε.

Light Sentence | valledesign.be

Στα αντικείμενα, τοποθετήσεις, γλυπτά, καταστάσεις που θα εκτεθούν στους πολιτιστικούς χώρους της πόλης του Βερολίνου, αλλά και στο ευρύτερο έργο της Hatoum, η αρχιτεκτονική και το design έχουν ιδιαίτερη σημασία όσον αφορά την απόδοσή τους. Διαφωτιστικό παράδειγμα αποτελεί το Light Sentence του 1992, που μια μηχανοκίνητη λάμπα κινείται ανάμεσα από ένα μεταλλικό πλέγμα, αλλοιώνοντας και διαμορφώνοντας δυναμικά τον χώρο μέσα από το αντίθετο του φωτός, τη σκιά. Ο χώρος και τα αντικείμενα, μαζί με το λογοπαίγνιο του τίτλου, ανοίγουν τον δρόμο σε ερμηνείες σχετικά με τη σωματική μας σχέση με πλαίσια που άλλοτε μπορεί να είναι κλουβιά, και άλλοτε το υλικό που -μέσω της επαφής του με το φως- μας αποκαλύπτει τις σκιές και διαταράσσει το ευρύτερο εξωτερικό και εσωτερικό μας περιβάλλον.

Light Sentence | elconfidencial.com

Αντίστοιχα, το έργο Remains (2018) συνεχίζει τη λειτουργία τού μεταλλικού πλέγματος σε άλλη κλίμακα, αυτή του επίπλου. Το πλέγμα παίρνει τη μορφή μιας τυπικής, οικείας καρέκλας που θα μπορούσε να βρίσκεται στο σαλόνι μας, και μέσα στο πλέγμα κλείνονται θραύσματα ξύλου σαν απομεινάρια κάρβουνου. Εκεί επιτυγχάνεται μια πολύ ενδιαφέρουσα ανοικειοποίηση του αντικειμένου, που είναι σε θέση να μας βάλει σε σκέψεις τόσο σχετικά με την κλιματική κρίση -σαν απόηχος και του έργου της Hot Spot (2009)- όσο και με την ύλη, και ενδεχομένως και πιο άυλες, αόρατες πτυχές της πραγματικότητας, που εγγράφονται σε ένα τόσο καθημερινό αντικείμενο. Με μια απλή μεταμόρφωση πετυχαίνει την ιδιάζουσα κατάσταση του ανοίκειου/uncanny, σαν σε ταινία τρόμου που το αρχετυπικό ξύλινο σπίτι με τη στέγη έχει πόρτες που τρίζουν ή ιδιαίτερους φιλοξενούμενους στη σοφίτα ή στο υπόγειο. “Μικρές” τροποποιήσεις στο υλικό και στη φόρμα ξυπνάνε συνειρμούς γύρω από τους τρόπους με τους οποίους μπορούμε να χρησιμοποιήσουμε ένα τόσο εύθραυστο αντικείμενο, αλλά και σε σχέση με το τι είδους πράγματα φυλακίζουν ή φυλακίζονται στο εσωτερικό του.

Hot Spot | theoriginalneon-neon.com -

Remains | artbasel.com

Παρόμοια πάλη με τα όρια αποτελεί, βεβαίως, και το έργο της Grater Divide (2002). Ένα διαχωριστικό που συναντά κανείς σε ένα νοσοκομείο ή σε ένα δωμάτιο για να αλλάζει κάποιος ρούχα, μετουσιώνεται σε ανάπτυγμα τρίφτη. Η διπλή αυτή μεταμόρφωση -τόσο της κλίμακας του τρίφτη, όσο και της υλικότητας και διαπερατότητας του διαχωριστικού- βάζει σε κεντρικό πλαίσιο το σώμα, όπως είχε κάνει και η πιο σημαντική της δουλειά Deep throat (1996), όπου σε εκείνη την περίπτωση είχε παρουσιάσει το εσωτερικό τοπίο του κορμιού της με μια ενδοσκοπική κάμερα. Στο Grater Divide, ένα διαχωριστικό ξεκινά διάλογο με τη φύση των ορίων και των συνόρων, ανακαλώντας την Παλαιστινιακή της καταγωγή. Οι τρύπες του θυμίζουν αραβικά masrabiya και η τυπική τους χρήση στα boudoir των γυναικών κατευθύνει ακόμη ευρύτερα τη συζήτηση. Τα διαχωριστικά, τελικά, αποκρύπτουν και προστατεύουν το σώμα και τις απόκρυφες στιγμές μας, ή έχουν το κοφτερό αποτέλεσμα του μεταλλικού ξύστρου; Η Mona Hatoum μάς ανοίγει αυτούς τους δρόμους και μας καλεί συνεχώς να τους περπατήσουμε.

.jpg)

.jpg)