Digital Fabrication στο εγχώριο design: Μια ανάλυση από τον Ευτύχη Ευθυμίου

DS.WRITER:

Vasilis Xifaras

Design: Ezio Blasetti, Danielle Willems, Pavlos Xanthopoulos. Fabrication: Decode Fab Lab

Το Digital Fabrication προσφέρει πολλές ευκαιρίες για ένα design διαφορετικό από το συνηθισμένο. Στην Ελλάδα, το Digital Fabrication απασχολεί τους δημιουργούς σε πειραματικό ακόμα επίπεδο. Λίγοι το επιλέγουν ώστε να φτιάξουν ποιοτικά έργα, μακριά από μια λογική μαζικής παραγωγής που συνήθως προσφέρει η αυτοματοποίηση. Ζητήσαμε από τον Ευτύχη Ευθυμίου, βιολόγο, σχεδιαστή και ακαδημαϊκό, να μας περιγράψει τι είναι αυτό που κάνει την ψηφιακή παραγωγή μοναδική.

Decode Fab Lab

Το πρώτο πιστοποιημένο Rhino Fab Studio στη χώρα χαρακτηρίζεται ως ένας δημιουργικός παιδότοπος, που στοχεύει στην κατανόηση και εκμάθηση των νέων τεχνικών κατασκευής πρωτοτύπων. Ο Ευτύχης Ευθυμίου είναι ο υπεύθυνος εκπαίδευσης και ο βασικός computational designer στο Decode Fab Lab. Μελετά κυρίως αυτοποιητικά συστήματα σχεδιασμού στη μεταψηφιακή συνθήκη. Αν και ασχολείται κυρίως με την αρχιτεκτονική, επιδίδεται σε κάθε σχεδιαστικό εγχείρημα με τον ίδιο ενθουσιασμό, είτε είναι product design, set design, live media ή απλά εικονογραφία.

Φωτ: decodefablab.com

Ποια είναι τα πλεονεκτήματα και τα μειονεκτήματα που φέρνει το Digital Fabrication στον σχεδιασμό; Είναι το κόστος του εξοπλισμού και των υλικών απαγορευτικό για πειραματισμούς;

Το digital fabrication είναι ένας όρος ομπρέλα, που καλύπτει μια μεγάλη γκάμα από τεχνικές κατασκευής που βρίσκονται γύρω μας εδώ και δεκαετίες. Συνδυάζοντας subtractive και additive manufacturing, δηλαδή μεθοδολογίες στις οποίες αφαιρούμε υλικό (πχ CNC) και μεθοδολογίες στις οποίες προσθέτουμε υλικό (πχ 3d printing), είμαστε πλέον σε θέση να δημιουργήσουμε ελεγχόμενα κυριολεκτικά οποιαδήποτε φόρμα, ασχέτως πολυπλοκότητας ή ζητημάτων ανάλυσης. Αυτό είναι το πρώτο θετικό που φέρνει το digital fabrication στο design, μια αίσθηση ότι όλα είναι πιθανά.

Το δεύτερο θετικό είναι η δυνατότητα mass customization. Η ψηφιακή κατασκευή φέρνει μια κατάρρευση της οικονομίας της κλίμακας, καθώς το κόστος για την κατασκευή 1.000 ομοίων αντικειμένων πλέον μπορεί να είναι ίδιο με αυτό 1.000 διαφορετικών παραλλαγών, είτε αυτά είναι προϊόντα, είτε facade panels για ένα κτίριο.

Στην πραγματικότητα, όμως, η μεγάλη επανάσταση έρχεται με ένα παρακλάδι της ψηφιακής κατασκευής, το rapid prototyping, δηλαδή τη δημιουργία σχεδιαστικών δοκιμών σε πραγματικό χρόνο. Με αυτόν τον τρόπο ο σχεδιαστής μπορεί να δοκιμάσει, να βελτιώσει, να βιώσει σε κάποιον βαθμό τα σχέδιά του, χωρίς να χρειαστεί να περάσει από μια αλυσίδα βιομηχανικής παραγωγής, με ένα κλάσμα του κόστους.

Το digital fabrication, λοιπόν, επαυξάνει τις δυνατότητες του σχεδιαστή, απελευθερώνει τις επιλογές που έχει για τις πιθανές επιλύσεις και επεκτείνει τον σχεδιασμό σε μεγαλύτερο βάθος. Ειλικρινά, δεν μπορώ να δω μειονεκτήματα, καθώς δεν αφαιρεί κάτι από την παλιά εργαλειοθήκη του σχεδιασμού, αλλά ανοίγει νέους δρόμους.

Το κόστος για να πειραματιστεί κανείς με την ψηφιακή κατασκευή δεν είναι απαγορευτικό, αλλά εξαρτάται από την εκάστοτε τεχνολογία. Ένας καλός επιτραπέζιος 3d printer κοστίζει πλέον αρκετά κάτω από 1000 ευρώ, ενώ το κόστος των υλικών είναι έως και αμελητέο. Κάθε αρχιτεκτονικό γραφείο, πχ, θα μπορούσε να έχει από έναν. Ένα CNC ή ένας laser cutter, από την άλλη, είναι σημαντικά ακριβότερα και χρειάζονται πιο εξειδικευμένη γνώση. Η καλύτερη λύση για να πειραματιστείς και να ξεκινήσεις, είναι να πας στο κοντινότερο fab lab. Όπως τα περισσότερα πράγματα, το digital fabrication είναι καλύτερο με παρέα.

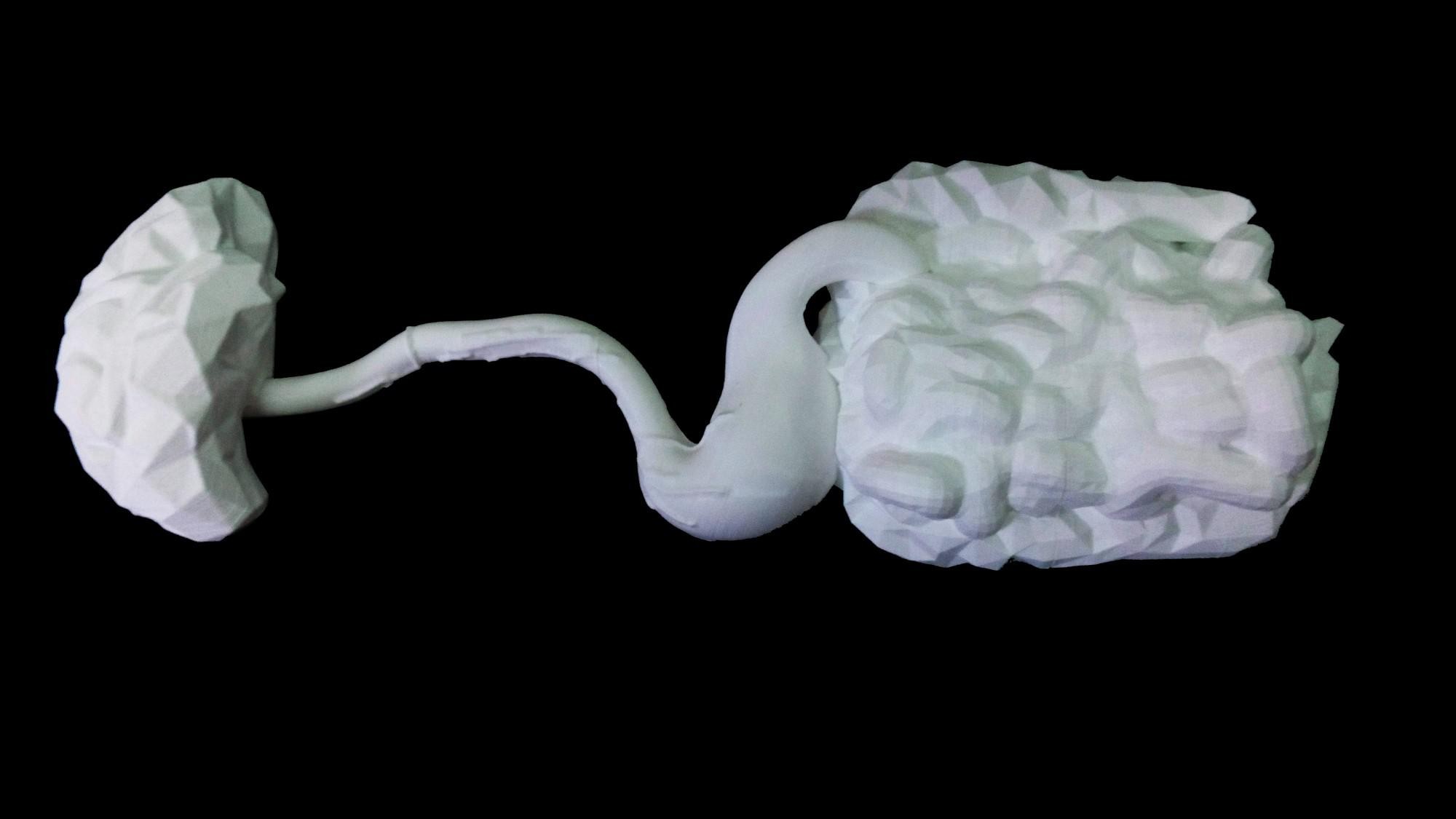

Athens Observatory 3D Print Model για το ΝΕΟΝ και την έκθεση «Adrián Villar Rojas - The Theater of Disappearance», 2017

Θα μπορούσε το εγχώριο design να βρει το μέσο έκφρασης και παραγωγής του σε ψηφιακά μέσα; Αν ναι, ποια κρίνετε εσείς ότι θα ήταν τα απαραίτητα εφόδια (προγράμματα, εξοπλισμός, εκπαίδευση και ενημέρωση);

Ας συγκρίνουμε δύο ταινίες. Η μία έχει γυριστεί το ‘60 και εξελίσσεται στο τότε, ενώ η άλλη έχει γυριστεί σήμερα αλλά η πλοκή εξελίσσεται στο ‘60. Η αισθητική και η εικόνα των δύο ταινιών είναι τελείως διαφορετική, και όχι απλά για λόγους εξέλιξης των τεχνικών μέσων. Η βασική διαφορά είναι ότι συνήθως, σε μια ταινία εποχής (όπως η σύγχρονη του παραδείγματος), βλέπεις μια φωτογραφία ενός κόσμου που δεν υπήρξε ποτέ, κατακλυσμένου από μόδα, design και αρχιτεκτονική της εποχής που αναφέρεται. Στην ταινία που γυρίστηκε όντως το ‘60, από την άλλη, βλέπεις δίπλα στον υλικό πολιτισμό τής συγκεκριμένης εποχής διάσπαρτα σε πληθώρα αντικείμενα των εποχών που προηγήθηκαν. Αυτοκίνητα του ‘40, κτίρια φθαρμένα με τεχνολογία στα κουφώματα του 19ου αιώνα, περαστικούς με ρούχα παλιά, καθημερινά, που δε μοιάζουν να βγήκαν από τα περιοδικά μόδας της εποχής. Μια εικόνα του πραγματικού σε αντίθεση με μιαν εικόνα σκηνογραφικής φαντασίας. Το ίδιο μπορεί να υποτεθεί και για την τεχνολογική εξέλιξη. Μόνο σε αφηγήματα τεχνομεσσιανισμού θα συναντήσεις έναν κόσμο όπου τα γραφεία θα λειτουργούν αποκλειστικά με τις πλέον σύγχρονες εφαρμογές design tech και digital fabrication. Στην πραγματικότητα, αυτό που θα δεις είναι μια υπέρθεση εποχών και τεχνικών.

Πιστεύω πως το εγχώριο design εδώ και χρόνια έχει ενσωματώσει για τα καλά τα ψηφιακά μέσα, τόσο δημιουργικά όσο και σε επίπεδο παραγωγής. Σε σχεδόν κάθε χώρο, τα έργα επιτελούνται ψηφιακά. Ακόμα και τα πλέον συντηρητικά αρχιτεκτονικά γραφεία, που θα λύσουν το κτίριο στο χέρι, θα καταφύγουν σε ψηφιακά μέσα, τουλάχιστον έστω για το arch vis, τα στατικά ή την επιμέτρηση. Στα πιο προοδευτικά γραφεία βλέπουμε πολύ μεγαλύτερο βαθμό ενσωμάτωσης, με την υιοθέτηση σύγχρονων τεχνικών computational design, BIM, simulation, VR κ.ά. Στο product design, τόσο σε επίπεδο ιδέας (form-finding) όσο και υλοποίησης (μηχανολογικά, σχεδιασμός parts ανάλογα με την τεχνολογία κατασκευής), τα αντικείμενα περνούν μέσα από ψηφιακές ατραπούς, ενώ, φυσικά, δεν μπορούμε με τίποτα να παραβλέψουμε τον ρόλο του rapid prototyping στη φάση του r&d. Από άποψη παραγωγής, δε γνωρίζω ούτε μία εταιρεία που να χρησιμοποιεί καλούπια που να έχουν φτιαχτεί χωρίς ψηφιακή κατασκευή σε κάποια φάση τους. Άρα τα ψηφιακά μέσα είναι εδώ.

Το πρόβλημα, λοιπόν, δεν έγκειται στο αν γίνεται χρήση ψηφιακών μέσων, αλλά σε τι επίπεδο βρίσκεται η γνώση των εργαλείων αυτών και στο ποιος είναι ο βαθμός εκμετάλλευσης των δυνατοτήτων τους. Σε πολύ μεγάλο βαθμό, η γνώση πάνω στα εργαλεία έρχεται μέσα από αυτομόρφωση των σχεδιαστών, και όχι μέσα από ακαδημαϊκή εμπλοκή. Και αν, μέσω του internet, είναι πλέον εύκολο να μάθει κανείς σχεδιαστικά εργαλεία, αυτό δεν ισχύει για την ψηφιακή κατασκευή.

Είναι πάρα πολύ σημαντικό αυτό που λέμε knowledge by doing και η κουλτούρα του making. Αυτό σημαίνει ότι οι σχεδιαστές χρειάζεται να δοκιμάσουν οι ίδιοι να δουλέψουν με τα εργαλεία, τόσο με τα ψηφιακά όσο και με τα συμβατικά. Να κόψουν στο laser, στο cnc, να τυπώσουν, να χειριστούν ρομποτικό βραχίονα, να κόψουν ένα ξύλο με τον τροχό, να βιδώσουν δέκα βίδες. Όλη αυτή η εμπλοκή δημιουργεί μία νοητική εργαλειοθήκη, στην οποία ο σχεδιαστής θα ανατρέξει όταν θα χρειαστεί να παραγάγει κάτι.

Όλα αυτά είναι κάτι που οι σχολές πρέπει να προσφέρουν απλόχερα. Τόσο με ανοιχτά εργαστήρια προτυποποίησης, με σύγχρονο εξοπλισμό και προσωπικό που θα βοηθήσει τους φοιτητές να κατασκευάσουν τις ιδέες τους, όσο και με διδασκαλία ψηφιακών μέσων, πλήρως ενταγμένη στο curriculum των συνθετικών μαθημάτων, από φρέσκο κόσμο με περιέργεια. Το βασικότερο βήμα είναι η πρόσληψη μεγάλου αριθμού νέων ακαδημαϊκών και επιστημονικού προσωπικού, η χρηματοδότηση, αλλά ταυτόχρονα χρειάζεται και αρκετή δουλειά σε επίπεδο προγράμματος σπουδών.

Εκτός σχολών, θα πρέπει να ανθίσει περισσότερο ο θεσμός των fab lab ως κέντρων εκπαίδευσης και πειραματισμού, αλλά και ανοικτής εργαλειοθήκης σε επίπεδο γειτονιάς. Στο Decode προσπαθούμε πάρα πολύ να λειτουργούμε προς αυτή την κατεύθυνση. Η πλέον δυσάρεστη έκβαση για τα fab lab είναι να αποτυπωθούν στη συνείδηση του κόσμου ως ενός είδους 3d φωτοτυπάδικα γειτονιάς.

Τώρα, σε σχέση με το τι χρειάζεται ένας designer, δε θα ήθελα να αναφέρω προγράμματα, αλλά θα πω ότι γενικά το βασικό skillset απαιτεί γνώση NURBS modeling & drafting, polygon modeling, volumetric modeling, computational design & analysis skills, visualization skills και γνώση τουλάχιστον των βασικών πρωτόκολων ψηφιακής κατασκευής (3d printing, laser cutting, CNC milling) και των περιορισμών τους.

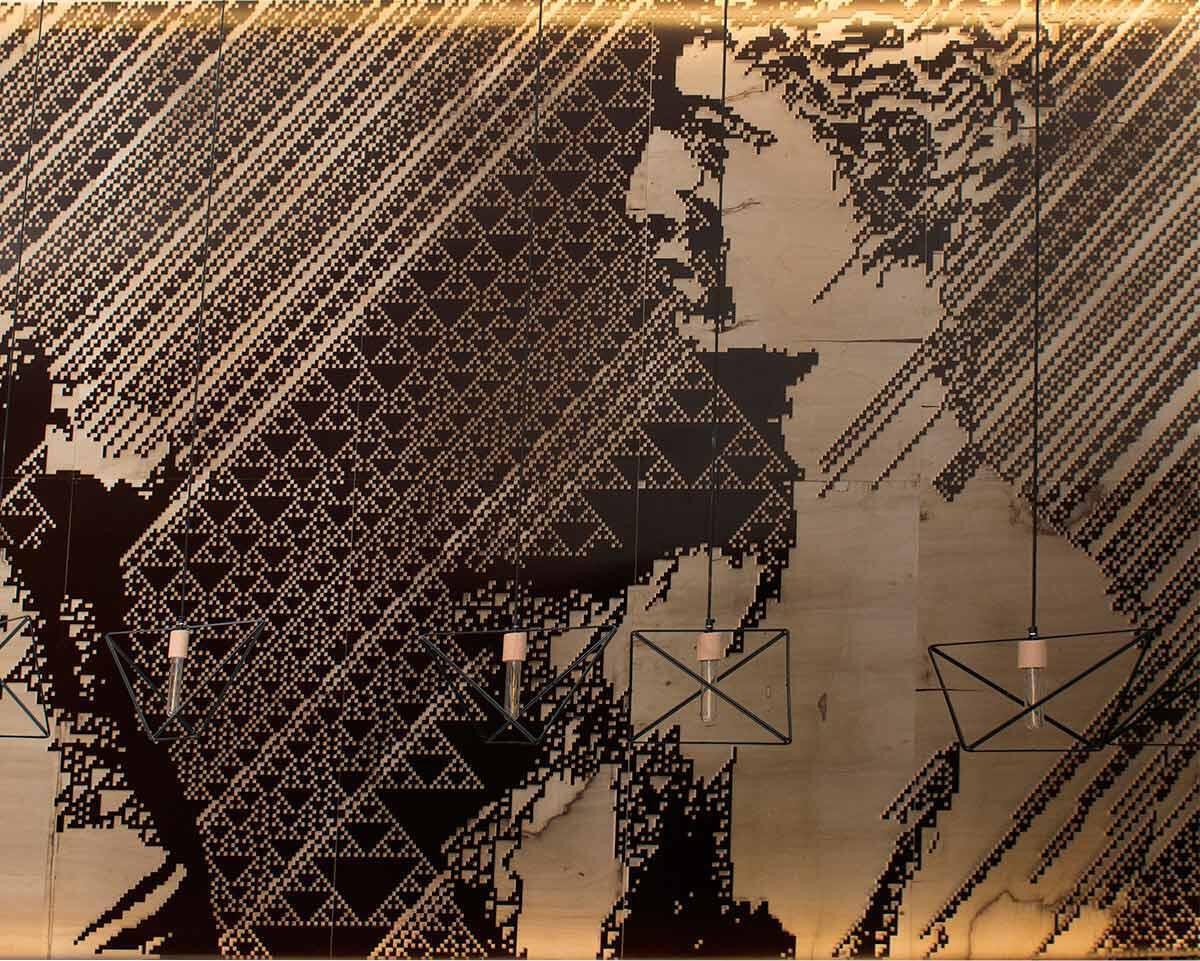

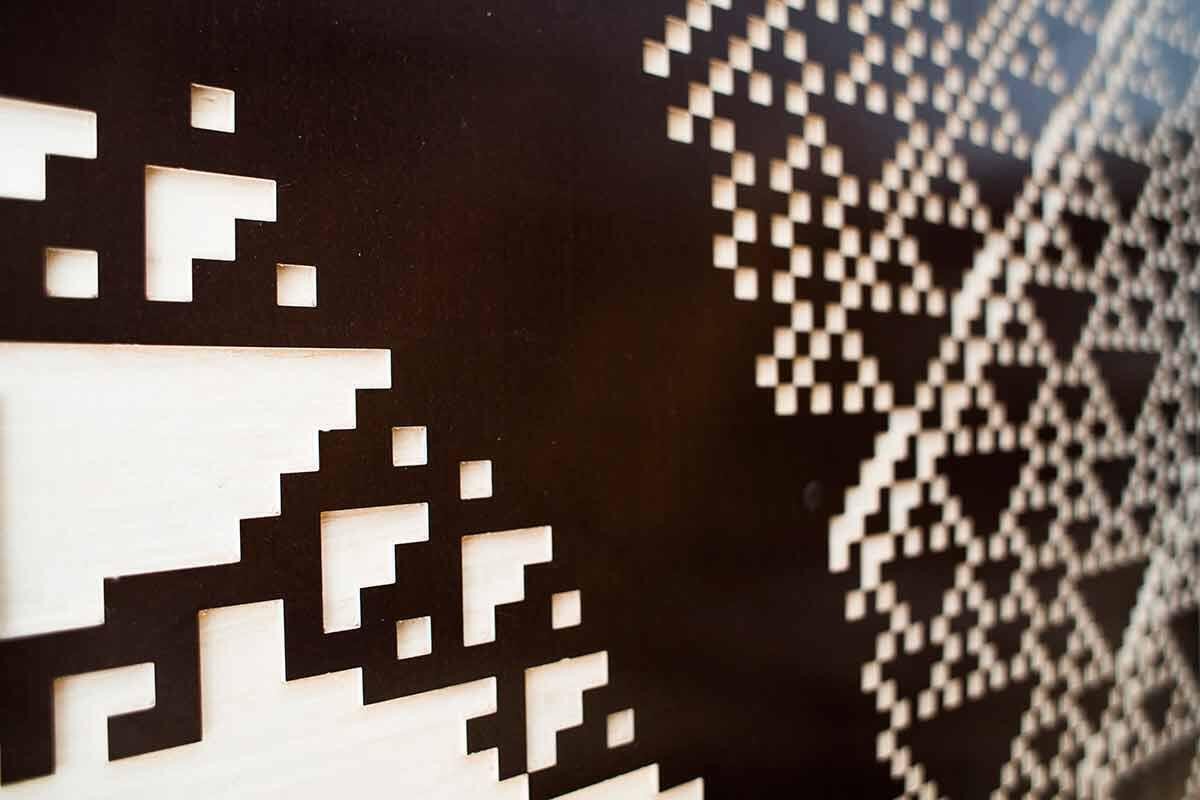

Mural για το Athens Lodge Boutique Hotel, 2018 | φωτ: Olga Stefatou

Θεωρείτε ότι ο ψηφιακός σχεδιασμός απειλεί τον ρόλο του designer; Υπάρχουν διακριτά όρια μεταξύ υπολογιστή και σχεδιαστή, και πώς προβλέπετε την εξέλιξη αυτής της σχέσης στο μέλλον;

Συγχώρεσέ με, αλλά νομίζω ότι είναι εντελώς αναχρονιστικό το ερώτημα στη βάση του. Και εξηγούμαι. Επίτρεψέ μου, για αρχή, να σε παραπέμψω στη διάσημη φράση τού Nicholas Negroponte στα τέλη του ‘90: "Like air and drinking water, being digital will be noticed only in its absence, not by its presence. Face it -the Digital Revolution is over", με την οποία ουσιαστικά κηρύττει την αρχή της μετα-ψηφιακής (post digital) εποχής. Στον post digital κόσμο όπου ανήκουμε, το ψηφιακό έχει μπει ολοκληρωτικά στη ζωή, εισερχόμενο ταυτόχρονα στη σφαίρα της καθημερινής πρακτικής και του τετριμμένου, αφήνοντας πίσω κάθε αίγλη επανάστασης, πρωτοπορίας κλπ. Και αυτή η απομάγευση είναι υπέροχη.

Ο ψηφιακός σχεδιασμός έχει εδραιωθεί εδώ και δεκαετίες, σε κάθε παρακλάδι τού σχεδιασμού, από την αρχιτεκτονική, στο product, industrial design κ.ο.κ. Αυτό έχει να κάνει τόσο με την τεχνολογία κατασκευής, που στη συντριπτική πλειοψηφία της είναι ψηφιακή, όσο και γενικότερα με το μέσο που μας φέρνει σε επαφή με το έργο. Το σύνολο της ζωής μας διαμεσολαβείται και περνάει μέσα από το ψηφιακό. Τα σχέδια που παράγουμε βιώνονται κυρίως μέσα από οθόνες, είναι λογικό να παράγονται με ανάλογες μεθόδους. Αλλά, ακόμα και αν παράγονται παραδοσιακά (1), στο χέρι, από τη στιγμή που παράγονται στο παρόν συγκείμενο, είναι ψηφιακά, έστω και μέσω εγελιανής άρνησης. Έχουμε πλέον δοκιμάσει από το δέντρο της γνώσης του καλού και του κακού, έχουμε επίγνωση της γύμνιας μας.

Άρα, με βάση τα παραπάνω, ο ψηφιακός σχεδιασμός είναι το πλαίσιο εντός του οποίου λειτουργούμε, το μέσο με το οποίο παράγουμε και τα industry standards με βάση τα οποία επικοινωνούμε. Μου είναι εξαιρετικά δύσκολο να δω πώς κάτι τέτοιο μπορεί να απειλεί τον ρόλο του designer, χωρίς να κάνω ένα από τα δύο ακόλουθα ατοπήματα. Το πρώτο είναι η επινόηση ενός τεχνοφοβικού παραδείγματος, το οποίο μπορώ να καταλάβω μόνο ως άμυνα απέναντι στην ανάγκη υιοθέτησης μιας διαρκώς εξελισσόμενης εργαλειοθήκης (2). Το δεύτερο -και εξαιρετικά πιο επικίνδυνο- είναι η θεώρηση του σχεδιασμού όχι ως μιας πρακτικής σύλληψης ιδεών, επινόησης χρήσεων και μορφών, διαρκούς παιχνιδιού με τις έννοιες και, ας το απενοχοποιήσουμε, με τη γεωμετρία, αλλά ως απλά μιας διαδικασίας τοποθέτησης γραμμών πάνω στο χαρτί. Με αυτή τη θεώρηση δεν μπορώ να επικοινωνήσω.

Σε κάθε περίπτωση, ο ψηφιακός σχεδιασμός είναι ένα μέσο, ένα εργαλείο για τη σκέψη, όπως όλα τα άλλα. Γιατί δεν ακούμε ποτέ την ερώτηση αν το μολύβι απειλεί τον ρόλο του σχεδιαστή, αν ο χάρακας επιβάλλει γεωμετρίες και έννοιες, αν ο διαβήτης καταπνίγει την ποιητική ασάφεια του ελεύθερου χεριού; Γιατί δε θεωρούμε το χαρτί ως διαβρωτική διαμεσολάβηση;

Όσον αφορά τα όρια σχεδιαστή και υπολογιστή, ποια είναι τα όρια μεταξύ βιρτουόζου πιανίστα και πιάνου με ουρά; Ή εργοδηγού και μπουλντόζας; Πού σταματάει το χέρι του αγρότη και ξεκινά η τσάπα ή το μάτι του βιολόγου και ξεκινά το μικροσκόπιο; Πού σταματά το στόμα και ξεκινά το δόντι; Δεν μπορώ να πω με ευκολία και σίγουρα, όχι χωρίς να επαναλαμβάνομαι. Αυτό όμως που βλέπω για το μέλλον είναι η απόλυτη απίσχναση των ορίων. Η ενσωμάτωση (integration) του ψηφιακού μόνο θα μεγαλώσει, τα εργαλεία θα γίνουν πιο intuitive, και ό,τι έχουμε μάθει για τον ψηφιακό σχεδιασμό θα ανατραπεί. Λέξεις όπως CAD, BIM, computational, volumetric θα γίνουν πολύ σύντομα μουσειακές, όπως ο παντογράφος. Το μόνο που έχουμε να κάνουμε είναι να τις χαρούμε όσο τις έχουμε δίπλα μας.

(1). Εδώ με τον όρο “παραδοσιακά” εννοώ με χαρτί, αν και πλέον το “παραδοσιακά” θα μπορούσε να αναφέρεται και σε Autocad, Photoshop και το σύνολο της συμβατικής ψηφιακής εργαλειοθήκης των τελευταίων 30 χρόνων.

(2). Σε αυτό μπορώ να απαντήσω ότι κι εγώ, συνέχεια βρίσκομαι στη θέση τού να μαθαίνω νέα εργαλεία, να ψάχνω νέους τρόπους να κάνω έστω και τα ίδια πράγματα με πριν, να τροφοδοτώ μια αχόρταγη περιέργεια για το νέο. Είναι διαρκώς αμήχανο, ζωογόνο και, σίγουρα, ο μόνος τρόπος να μη μας ξεπεράσουν οι καιροί.

.jpg)