Σχεδιαστικές Αφηγήσεις

DS.WRITER:

Tasos Giannakopoulos

Κεντρική Εικόνα: Gigantomachy, Parthenon | ytimg.com

Ideas generate realities.

Οι ιδέες παράγουν πραγματικότητες.

David Graeber

Κατασκευάζουμε ιδέες για τον εαυτό μας, και αυτές κατασκευάζουν εμάς με τη σειρά τους. Οι ιστορίες που λέμε στον εαυτό μας είναι ένα από τα πιο δυνατά εργαλεία που έχουμε στη διάθεσή μας. Είτε κανείς το πιάσει από τη μεριά της μεσαιωνικής θεολογίας και τη δύναμη της πίστης, ή από τη μεριά της νευροδιάδρασης (neurofeedback), το πιο σύγχρονο και γοργά αναπτυσσόμενο μέτωπο των νευροεπιστημών, το συμπέρασμα είναι λίγο πολύ το ίδιο. Άλλοι πολλοί κλάδοι και, κυρίως, η καθημερινή μας εμπειρία, επιβεβαιώνουν πως οι ιστορίες, οι μεταφορές, οι μυθοπλασίες, οι ιδεολογίες, όσα κατασκευάζουμε διαμέσου της φαντασίας μας γενικά, επιδρούν σε μικρότερο ή μεγαλύτερο βαθμό στην πραγματικότητα την ίδια, είτε ως πρότυπα πάνω στα οποία στήνουμε τις ζωές και τη συμπεριφορά μας είτε ως παραδείγματα προς αποφυγή ή/και προειδοποίηση.

Όλες αυτές οι προσεγγίσεις κινούνται γύρω από το γενικότερο και πολυδαίδαλο θέμα της αναπαράστασης, το οποίο έχει απασχολήσει την ανθρωπότητα, και ιδιαίτερα τον δυτικό πολιτισμό, από τα αρχαία χρόνια. Πρόκειται δηλαδή για το φανταστικό (fiction), το οποίο βρίσκεται ανάμεσα στο αληθινό και το ψεύτικο και συμπεριλαμβάνει τις μεταφορές, τη γλυπτική, τις ταινίες, τις σειρές στο Νetflix, ακόμη και την αρχιτεκτονική και το design. Σε μια από τις μετώπες του Παρθενώνα θα δούμε το φανταστικό γεγονός της Γιγαντομαχίας, όπου οι θεοί αντιμάχονται τους Γίγαντες, οι οποίοι στη συγκεκριμένη απεικόνιση έχουν ανθρώπινη και όχι τερατόμορφη αναπαράσταση όπως συνηθιζόταν, σημειώνοντας κάτι για τον ηθικό αγώνα που λαμβάνει χώρα ξεχωριστά μέσα στον καθένα μας, αλλά και συλλογικά ανάμεσά μας.

Charles Perrault | wikimedia.org

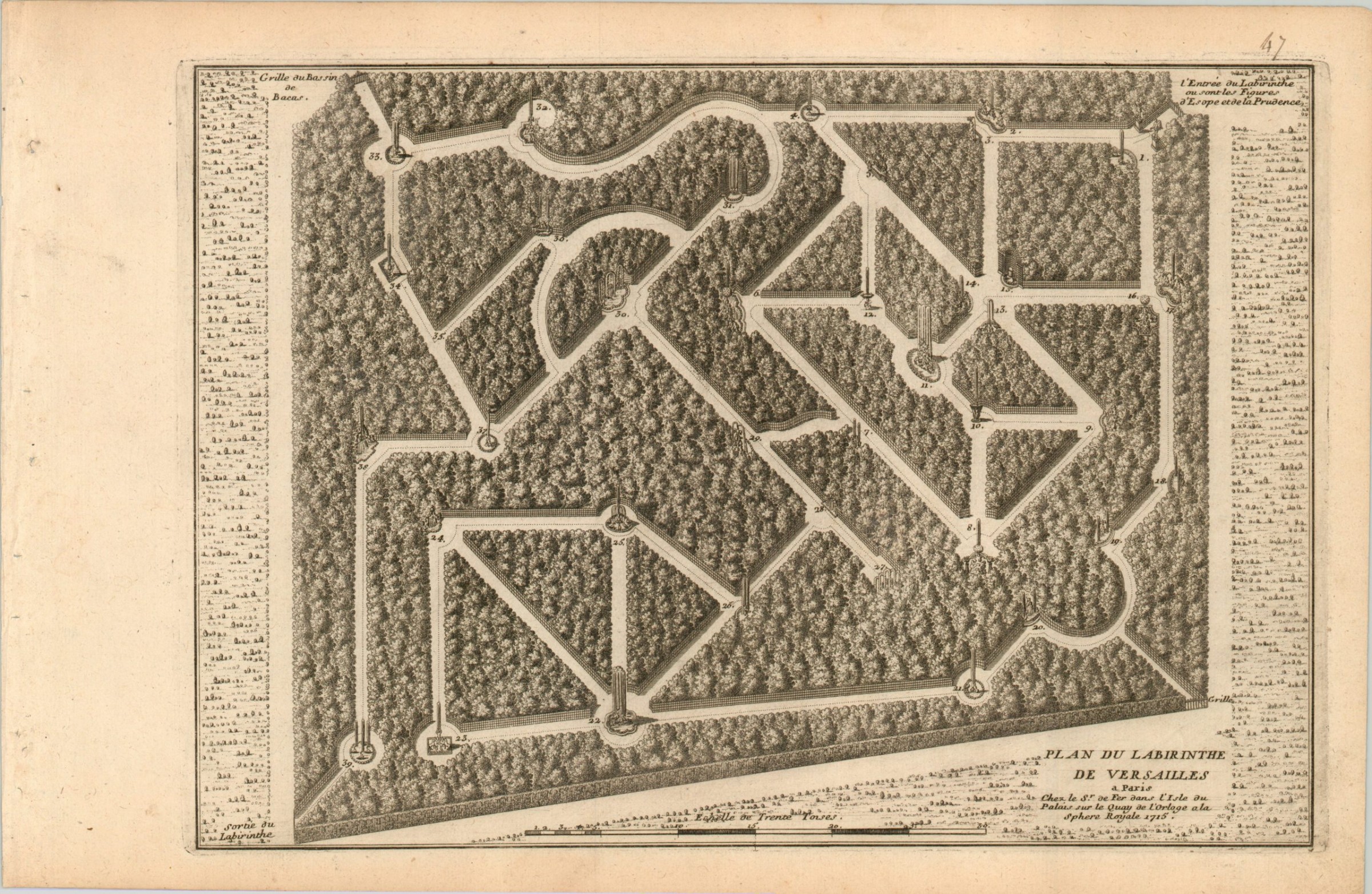

Plan du Labyrinthe de Versailles | curtiswrightmaps.com

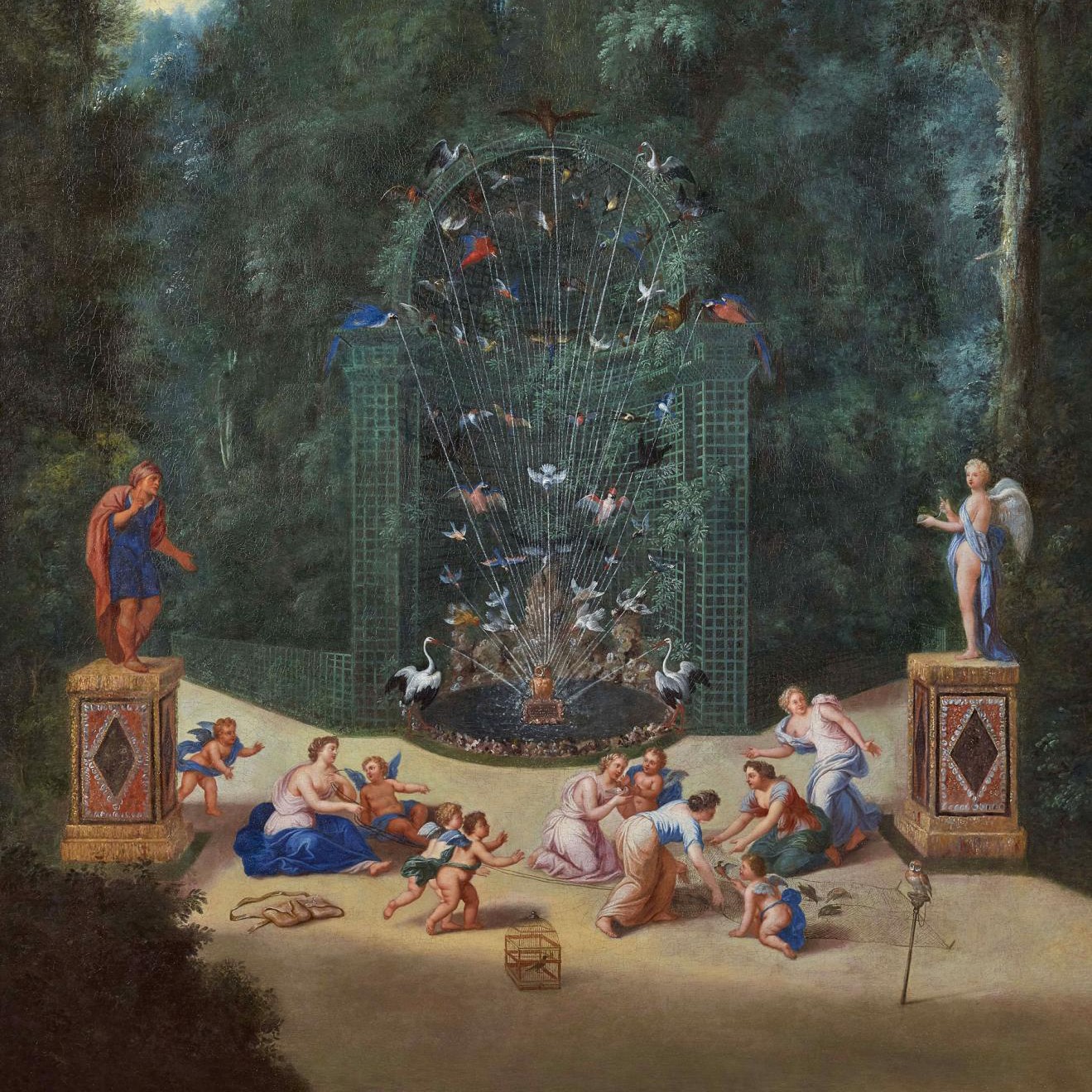

The King’s Animals | chateauvrsailles.fr

O Charles Perrault, που του αποδίδεται ο τίτλος του δημιουργού του λογοτεχνικού είδους του παραμυθιού και που είναι πιο γνωστός για τη συγγραφή της Κοκκινοσκουφίτσας, της Σταχτοπούτας, του Παπουτσωμένου Γάτου και πολλών άλλων παραμυθιών, πάνω στα οποία η Disney έστησε την αυτοκρατορία της, συνεργάζεται το 1666 με τον αρχιτέκτονα τοπίου του Λουδοβίκου του 14ου, τον André le Nôtre, για τον σχεδιασμό ενός κήπου/λαβυρίνθου, μέρος των κήπων των Βερσαλλιών. Οι βασιλικοί κήποι ήταν εκείνη την εποχή -που δεν υπήρχε η τηλεόραση- μέρος της ψυχαγωγίας των αριστοκρατών και των βασιλιάδων, που χειραγωγούσαν τη φύση στα γεωμετρικά σχήματα που επιθυμούσαν και που μετέτρεπαν μεγάλα κομμάτια γης στο βαρετό, μονοποικιλιακό γκαζόν, απλά και μόνο επειδή μπορούσαν και δεν χρειαζόταν να καλλιεργήσουν τίποτα πάνω τους, μιας και τη διατροφή την είχαν σίγουρα εξασφαλισμένη. Στους λαβυρινθώδεις κήπους, που ήταν της μόδας τότε, λάμβαναν χώρα τα παιχνίδια αποπλάνησης των ευγενών σε ένα αρχιτεκτονικό παιχνίδι περιπλάνησης, επιτηδευμένης απώλειας του προσανατολισμού, εμφάνισης και απόκρυψης, πολύ κοντινό με τις σωματικές περιπτύξεις που συνέβαιναν στο εσωτερικό τους. Ο Perrault, λοιπόν, τοποθετεί στην είσοδο τον θεό Έρωτα και τον γνωστό σε όλους μας Αίσωπο, καθώς επίσης και τετράστιχα από τους μύθους του, σε 39 κρήνες μέσα στον λαβύρινθο, με σκοπό να λειτουργεί σαν υπενθύμιση και πυξίδα η σοφία των ιστοριών του, ούτως ώστε να μη χαθούν οι αριστοκράτες σε παιχνίδια ερωτικά.

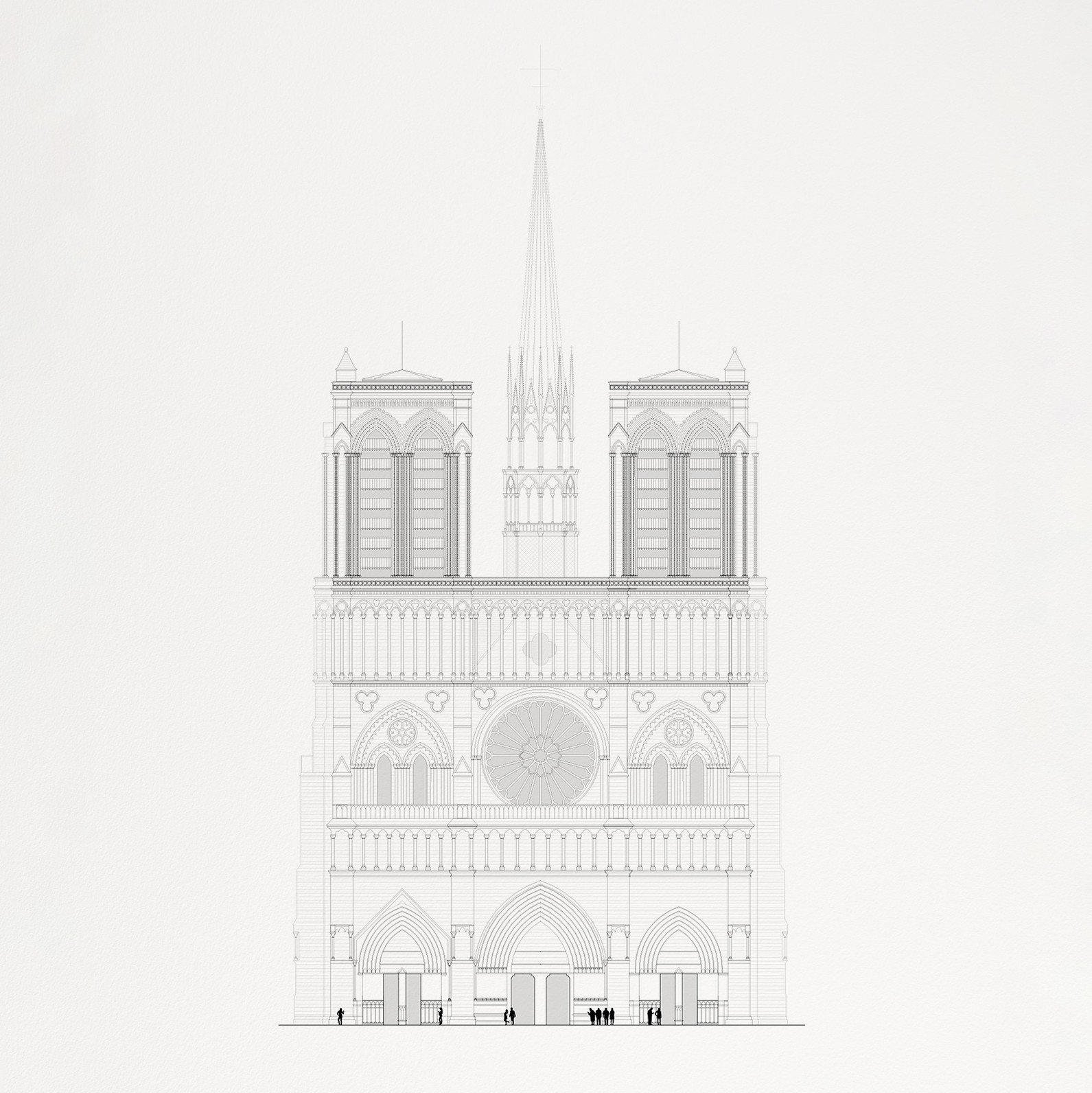

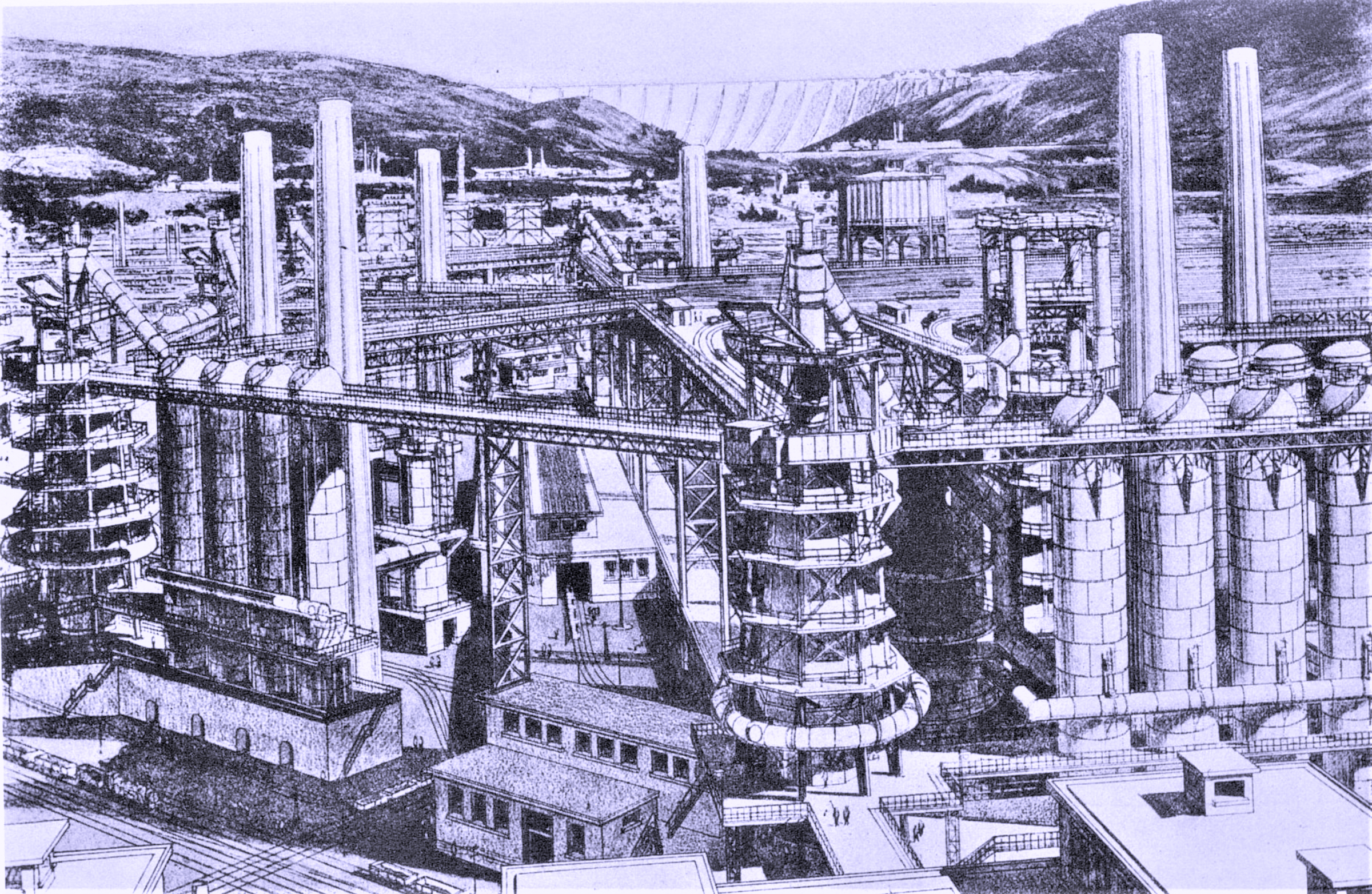

Αυτές είναι δύο μονάχα χαρακτηριστικές προσεγγίσεις δύο χαρακτηριστικά διαφορετικών κοινωνιών. Από τα αγάλματα στην αποκατάσταση της Notre Dame του Eugène Viollet-le-Duc με τα gargoyle, τους Εβραίους και τα τέρατα, στην προγραμματικά οργανωμένη ουτοπία της Cité Industrielle του Tony Garnier, μέχρι το φανταστικό project του Danteum του Giuseppe Terragni ή το σύγχρονο fiction design που προσπαθεί να φανταστεί φόρμες για μια μετα-ανθρωπιστική (post-humanist) κοινωνία, που συμπεριλαμβάνει τόσο ανθρώπους όσο και άλλα είδη, μηχανές και υβρίδια και οτιδήποτε ενδιάμεσο στις σκέψεις και τους στόχους της, και η λίστα δεν έχει τέλος.

Notre-Dame de Paris | desplans.com

Gargoyle thinking, Notre Dame | thedailydeast.com

Cité industrielle, Tony Garnier | wikimedia.org

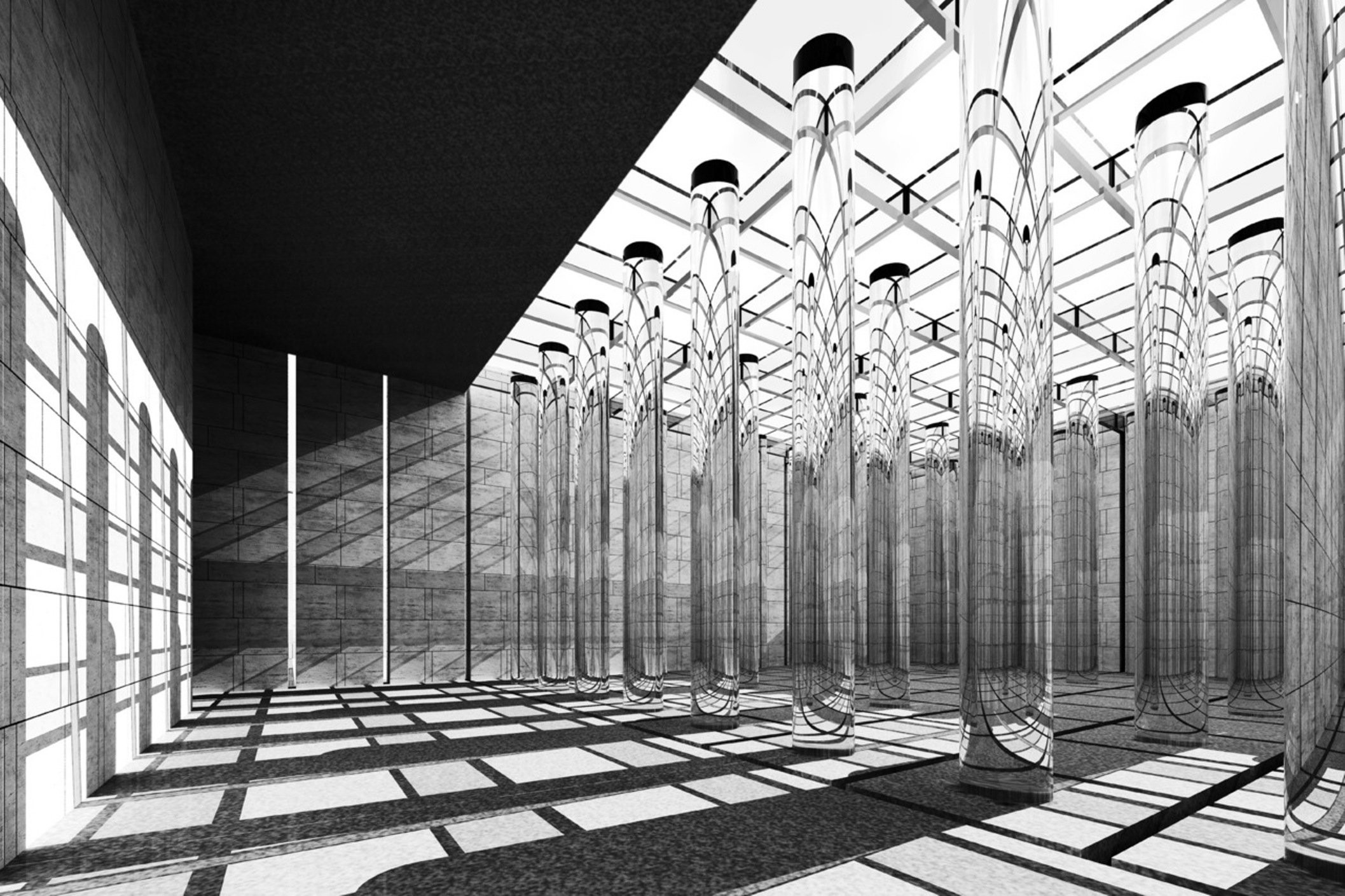

Danteum, Giuseppe Terragni | twimg.com

Το design, πιο συγκεκριμένα, εξερευνά τον τελευταίο καιρό αυτό που αποκαλεί speculative design και αποτελεί μέρος τής παραπάνω γενεαολογίας. Μας ζητά να κινηθούμε πέρα από τις προσδοκίες και τις πρακτικές των χρηστών και να φανταστούμε πώς τα σχέδιά μας θα επηρεάσουν μελλοντικές κοινωνίες. Δεν λύνει -απαραίτητα- προβλήματα όπως κάνει το prototyping, ούτε προσπαθεί να προβλέψει το μέλλον, και δεν είναι σκέτη κριτική. Ασχολείται με δυνατότητες, περισσότερο από ό,τι ασχολείται με πιθανότητες, και μας ωθεί να σκεφτούμε τις προτιμήσεις μας σε σχέση με μια σειρά από πιθανά μέλλοντα και να αναλογιστούμε πώς τα αντικείμενα και οι χώροι που σχεδιάζουμε εξυπηρετούν ή δυσχεραίνουν τις προσπάθειές μας να κατασκευάσουμε αυτά τα μέλλοντα. Μια κοντινή και δημοφιλής αναφορά είναι η τηλεοπτική σειρά Black Mirror, και μια πιο εξεζητημένη, ενδεχομένως, η έκθεση Reprodutopia από τους Next Nature Network.

Reprodutopia | nextnature.net

Οι αναπαραστάσεις πάνω στο αρχιτεκτονικό μέλος, από το αρχιτεκτονικό μέλος και στην περιήγηση αυτού εσωτερικά και εξωτερικά, είναι μέρος της λειτουργίας αρχιτεκτονικού μέλους. Η αρχιτεκτονική και το design κάτι αναπαριστούν. Η πραγματικότητα παραμένει η σταθερή αναφορά τους, αλλά, όταν εκτελούνται καλά, ξεφεύγουν των περιορισμών τους. Είτε είναι κατασκευασμένες πραγματικότητες ή φανταστικά έργα, δημιουργούν τις ιστορίες μέσα στις οποίες ζούμε, ή/και μέσα από τις οποίες φανταζόμαστε. Όταν ξεθωριάσουν τα λόγια, όταν το zeitgeist μάς εγκαταλείψει, θα υπάρχει πάντα το άφατο γεγονός της αρχιτεκτονικής και του design, να επαναλαμβάνεται ως μία οπτική, σωματική, νοητική πραγματικότητα που θα προσφέρεται σε εμάς για ανάγνωση. Ένα δεδομένο από το οποίο θα αντλούμε πληροφορίες για τις ιστορίες που λέμε για το παρελθόν, το παρόν και το μέλλον μας.

.jpg)