Post Binary Design: Στον δρόμο για μια θεμελιώδη αλλαγή

DS.WRITER:

Ιωακειμίδου Χριστίνα

Πηγή Κεντρικής Εικόνας: media-cldnry.s-nbcnews.com

Έχει περάσει κάτι περισσότερο από ένας αιώνας, από τότε που ο C.R. Mackintosh επιμελήθηκε τον σχεδιασμό ενός από τα κτίρια του Glasgow School of Art (1897-1909), ενός κτιρίου που όχι μόνο έδωσε φήμη στον αρχιτέκτονα, αλλά και που αποτέλεσε το πρώτο κτίριο όπου το φύλο δεν στάθηκε η αφορμή για διαχωρισμό των εκάστοτε χώρων. Ωστόσο, δυστυχώς το συγκεκριμένο έργο του Mackintosh ήταν η εξαίρεση και όχι ο κανόνας για την εξέλιξη του αρχιτεκτονικού σχεδιασμού και του design προς μία κατεύθυνση, που θα έχει ως σκοπό τη συμπερίληψη. Μελέτες -με σημαντικότερες αυτές των Β. Colomina, Paul Preciado και Joel Sanders- για μία non-gender, non-binary προσέγγιση, έχουν απασχολήσει την κοινότητα και είναι ικανές να βελτιώσουν τον τρόπο με τον οποίο τα άτομα προβάλλονται διαμέσου του χώρου.

Η αρχιτεκτονική και το design ως τρόπος αναπαράστασης

Είναι αληθές, ότι από πάντα η κοινωνία (από οτιδήποτε αφορούσε την καθημερινότητα μέχρι και τον αρχιτεκτονικό σχεδιασμό του χώρου -δημοσίου και ιδιωτικού) λειτουργούσε ως ένας τρόπος σήμανσης της κοινωνικής και οικονομικής κατάστασης του εκάστοτε ατόμου, καθώς και του φύλου του. Από την απαγόρευση των γυναικείων συμμετοχών στους Ολυμπιακούς Αγώνες της αρχαιότητας, αλλά την ταυτόχρονη ανάδειξη των γυμνών γυναικείων αγαλματικών σωμάτων, έως τους γυναικωνίτες και τα ξεχωριστά υπνοδωμάτια των συζύγων του Leon Battista Alberti στην Αναγέννηση, το φύλο διαχωρίζεται, σεξουαλικοποιείται και απομονώνεται, για να μην προκαλεί. Και παρόλη την προσπάθεια συνύπαρξης χωρικά των δύο φύλων, με εξέχουσα περίπτωση, όπως προαναφέρθηκε, το The Glasgow School of Art του C.R. Mackintosh, ο διαχωρισμός βάσει φύλου ή σεξουαλικότητας παραμένει ορατός. Φυσικά, εδώ και μερικούς αιώνες αυτός ο διαχωρισμός και το αίσθημα ντροπής της σεξουαλικότητας δεν αφορούν μόνο την κοινότητα των straight ατόμων, και κυρίως των γυναικών. Η μεγαλύτερη πληγή και απομόνωση παρατηρείται στην LGBTQ+ κοινότητα, καθώς τα μέρη «φιλοξενίας» ομοφυλόφιλων ζευγαριών τις περισσότερες φορές ή θα αποσιωπώνται πλήρως είτε θα μένουν θαμμένα σε χώρους που προορίζονται για straight άτομα.

Μία πολύ ενδιαφέρουσα παρατήρηση της Patricia White για την «απόκρυψη» της gay σεξουαλικότητας, στο Sexuality and Space (1992) της B. Colomina, αναφέρεται στο σκηνοθετημένο από τον Robert Wise θρίλερ The Haunting (1963). Η ταινία καταφέρνει να αναγάγει ένα σπίτι, το Hill House, σε ένα μέρος όπου η κεντρική ηρωίδα, Eleanor, εξερευνά τη λεσβιακή της σεξουαλικότητα, αποκτώντας παράλληλα μία περίεργη εξάρτηση από το σπίτι, το οποίο στο παρελθόν ήταν τόπος θανάτου αρκετών γυναικών. Σύμφωνα με τη White, αν και τελικώς η λεσβιακή επιθυμία ηττάται (η ηρωίδα πεθαίνει στο σπίτι), παραμένει εκεί, χωρίς να ξεχαστεί.

Σκηνή του The Haunting | Πηγή εικόνας: m.media-amazon.com

Την ίδια στιγμή, το άρθρο της Elizabeth Grosz στο ίδιο σύγγραμμα, μας φέρνει σε μια περισσότερο μεταμοντέρνα οπτική της σεξουαλικότητας και του χώρου, αναφέροντας: “the city is one of the crucial factors in the social production of (sexed) corporeal bodies: the built environment provides the context … for most contemporary … forms of the body.”. Ωστόσο, η ίδια, δυστυχώς, δεν ανέπτυξε περαιτέρω τη συγκεκριμένη ιδέα.

Εντούτοις, από τα παραπάνω γεννιούνται δύο ερωτήματα: ποια θα έπρεπε να είναι η προσέγγιση της θεωρητικής έρευνας και πρακτικής εφαρμογής μιας non-binary αρχιτεκτονικής ανάπτυξης και design, και ποια είναι η θέση της μοντέρνας και μεταμοντέρνας τάσης στην καθιέρωση των «συνόρων των φύλων» στον χώρο;

Από την “Τechnology of gender” στις μελέτες του Masculinity

Από τις έρευνες τόσο του Foucault για τη σεξουαλικότητα και τον όρο ‘technology of sex’, όσο και της Teresa de Lauretis για την ‘Τechnology of gender’, φτάνουμε στη μελέτη της αρρενωπότητας στον αρχιτεκτονικό σχεδιασμό, η οποία μέχρι τότε είχε παραμεληθεί αρκετά. Ίσως το θέμα θεωρούνταν αμελητέας σημασίας, αφού, μέχρι και τη δεκαετία του 1990 -όπου και πρωτοάρχισαν οι έρευνες- ο δημόσιος αλλά και ο ιδιωτικός χώρος που ήταν, θα λέγαμε, σε «κοινή θέα», προορίζονταν για τους ετεροφυλόφιλους λευκούς άνδρες.

Τομή σε αυτή τη νοοτροπία σχεδιασμού και θεωρητικής προσέγγισης στον κλάδο αποτέλεσε η έρευνα των Beatriz Colomina και Leslie Kaynes Weisman, ενώ η επέκταση της μελέτης των χώρων με βάση το φύλο και συγκεκριμένα την queer κοινότητα, έφερε μια ευρύτερη συζήτηση για την αρχιτεκτονική και τη σεξουαλικότητα. Συγχρόνως, η δουλειά των Colomina και Weisman άνοιξε τον δρόμο για queer μελετητές, όπως ο Aaron Betsky, ο Henry Urbach και ο Joel Sanders, οι οποίοι εισήγαγαν στην έρευνα τον όρο «παραγωγή του ανδρισμού» («production of masculinity»). Ο τελευταίος μάλιστα, στο βιβλίο του Stud: Architectures of Masculinity (1996), περιεργάζεται τα τέσσερα καθορισμένα μοτίβα (dressing wall surfaces, demarcating boundaries, distributing objects, and organising gazes), η επανάληψη των οποίων και η ορατότητά τους στην αρχιτεκτονική σύνθεση είναι σε θέση να διαμορφώσουν το φύλο. Έτσι, όσο περισσότερο ορατά και επαναλαμβανόμενα είναι αυτά τα μοτίβα σε όλους τους χώρους της καθημερινότητας, τόσο ενισχύεται η συνείδηση του φύλου, εν προκειμένω η αρρενωπότητα των ατόμων. Παρ' όλ' αυτά, το βιβλίο τελειώνει με το παράδοξο ότι πολλά από τα διακοσμητικά μοτίβα των κατεξοχήν «straight χώρων», όπως μοναστηρίων κτλ., χρησιμοποιούνται και στη διακόσμηση των queer χώρων, με κορύφωση της αντίφασης να αποτελούν οι δημόσιες τουαλέτες, αφού αυτές -αν και διαχωρισμένες- καταλήγουν να είναι χώροι σεξουαλικών συναντήσεων πολλών queer ατόμων.

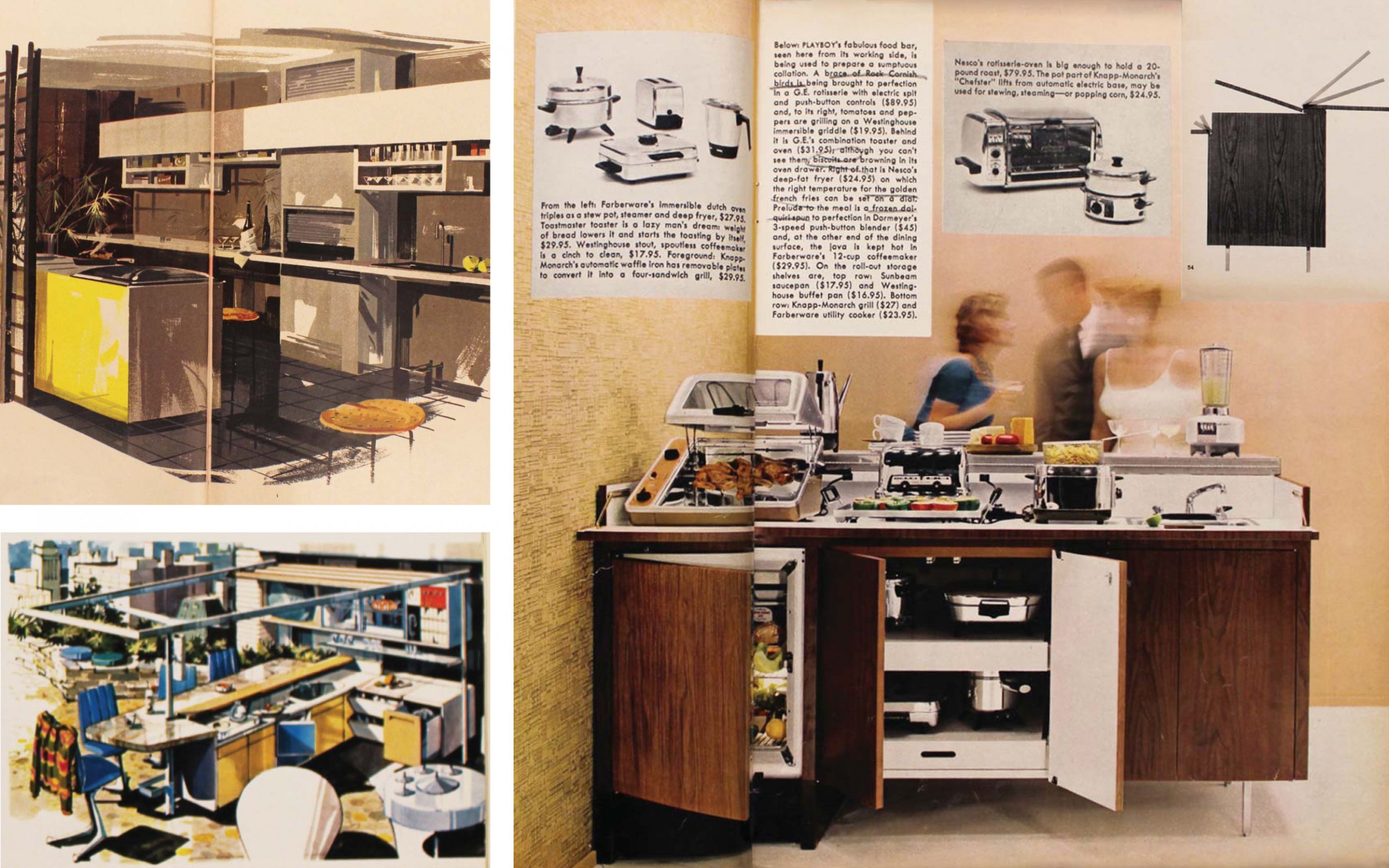

Playboy Penthouse Apartmen | Πηγή εικόνας: images.squarespace-cdn.com

Το ερώτημα, όμως, για το πώς πρακτικά επιτεύχθηκε αυτή η «ορατότητα της αρρενωπότητας», απαντάται, αν κάποιος σκεφτεί το Playboy Penthouse Apartment, στο οποίο γίνεται αναφορά στο βιβλίο του Sanders και εκτενής ανάλυση στη διατριβή του Paul Beatriz Preciado. Η δημοσιευμένη το 2014 διατριβή θεωρεί την οικονομία της επιθυμίας ως αυτή που άλλαξε την κατανόηση της αρρενωπότητας στη μεταπολεμική Αμερική, ενώ με τη φράση ‘mythical masculinity, able to withstand the heterosexual crisis during the 20th century and to confront the challenges posed by feminine liberation and the transgender utopia’, περιγράφει την κατάσταση που επικρατούσε, και ίσως σε πολλές περιπτώσεις συνεχίζει να επικρατεί, στις δυτικές κατά βάση κοινωνίες. Η αναφορά στις επαύλεις του Hugh Hefner ως ‘’alternative erotic topos to the suburban family house’ and with that ‘the possibility of a further ‘revolution’, one that was political and sexual’, θέτει τα θεμέλια για την αλλαγή του τρόπου κατανόησης της θέσης του straight άνδρα μέσα στο σπίτι, το οποίο, κατά την Colomina, λειτουργούσε σαν σκηνικό όπου η γυναίκα είτε βρισκόταν κρυμμένη στα πιο ιδιωτικά δωμάτια είτε γινόταν ορατή πάντα μέσω του ανδρικού βλέμματος. Επιπλέον, σύμφωνα με την ίδια, η παραπάνω λογική αντικατοπτρίζεται και στον σχεδιασμό εσωτερικών χώρων των Adolf Loos και Le Corbusier, οι οποίοι, αν και σχεδίαζαν με βάση την πρακτικότητα, στην ουσία επέτειναν τη νόηση του σπιτιού βάσει φύλου. Aυτό ήταν που κατά τους δύο ερευνητές άλλαξε λόγω του Penthouse Apartment του Playboy, το γεγονός ότι, όπως αναφέρεται στη διατριβή: ‘not only ways of seeing, but also ways of segmenting and inhabiting space, along with affects and modes of pleasure production’. Έτσι, η σεξουαλική ευχαρίστηση δεν είναι πλέον πίσω από τις κλειστές πόρτες των υπνοδωματίων του Alberti, αλλά είναι πανταχού παρούσα και ορατή, αφαιρώντας της την αίσθηση της ντροπής.

Σύγχρονες προσπάθειες για μια non-binary αρχιτεκτονική

Οι σκέψεις των μελετητών, όπως των B. Colomina, P.B. Preciado και J. Sanders, αναμφισβήτητα άνοιξαν τον δρόμο για μία διαφορετική προσέγγιση στις θεωρίες της χωρικής αναπαράστασης και σχεδιασμού, και τον τρόπο που αυτές λειτουργούν και επηρεάζουν το φύλο. Από τη μία πλευρά ο Sanders εξερευνά τον βιοτεχνολογικό σχεδιασμό, ούτως ώστε να παρέχει στα άτομα μέρη που στοχεύουν σε μία ελεύθερη, non-binary συνύπαρξη, ενώ η μελέτη του Preciado αποδεικνύει ότι το φύλο και η σεξουαλικότητα μπορούν να υπερβούν κάθε στερεοτυπικά παγιωμένη σεξουαλική ταυτότητα.

Ίδιες προσπάθειες για την επίτευξη της ουδετερότητας των χώρων με σκοπό τη δημιουργία μη-ετεροκανονικών κοινωνιών, αρχίζουν να προβάλλονται και να δίνουν κάποια ενθαρρυντικά στοιχεία για το μέλλον. Στόχος πλέον του αρχιτεκτονικού σχεδιασμού και interior design είναι η συμπερίληψη όλων των ατόμων στους δημόσιους και ιδιωτικούς χώρους, ενώ η εποχή που σταδιακά η ισότητα όλων δεν θεωρείται ένα απλό στοιχείο ανεκτικότητας, αλλά ουσιαστικής αποδοχής, φαίνεται ότι έχει ξεκινήσει. Για να προχωρήσουμε όμως παρακάτω, πρέπει να εντοπίσουμε και να κατανοήσουμε πόσο βαθύ είναι το πρόβλημα. Η Hannah Rozenberg, απόφοιτη του Royal College of Art, μας το δείχνει με τον πιο εύκολο και κάπως αναπάντεχο τρόπο. Το Βuilding Without Bias είναι μία εφαρμογή, που επιμελήθηκε η ίδια με τη βοήθεια ενός φίλου της, στην οποία μετράται, μέσω ενός αλγορίθμου παρόμοιου με αυτόν της Google Translate, πόσο ταυτισμένη είναι η κάθε λέξη με τον αρσενικό ή θηλυκό γλωσσικό προσδιορισμό. Έτσι, οι λέξεις μπετόν ή ατσάλι ταυτίζονται μέσω των ‘gender units’ (GU) με το αρσενικό φύλο, ενώ το γυαλί ή η κουζίνα με το θηλυκό.

Πηγή Εικόνας: archdaily.com

Μία ακόμα πρωτοβουλία της Rozenberg είναι ο σχεδιασμός διαφόρων κτιρίων και ανοιχτών χώρων στην περιοχή St. James του Λονδίνου, που χαρακτηρίζεται από τα gentlemen’s clubs και το υπερβολικά ανδροκρατούμενο στοιχείο. Παίρνοντας τα αντικείμενα που στην κλίμακα του Βuilding Without Bias έχουν GU (μονάδα μέτρησης της κλίμακας) μηδέν, η Rozenberg μπόρεσε να δημιουργήσει χώρους πλήρως απαλλαγμένους -βάσει του αλγορίθμου- από το έμφυλο στοιχείο, επιτυγχάνοντας να δείξει ότι υπάρχει τρόπος για την ουδετερότητα του σχεδιασμού. Ωστόσο, η ίδια δηλώνει πως τα αποτελέσματα δεν είναι πλήρως non-binary, καθώς η τελική εικόνα θα μετρηθεί, πάλι από software, για να επιβεβαιωθεί η ουδετερότητά της.

Η Rozenberg χρησιμοποιεί στοιχεία όπως τη γλώσσα και την τεχνολογία, ούτως ώστε να επιτύχει την επιθυμητή συμπερίληψη όλων στον χώρο. Από αυτό καταλαβαίνουμε ότι, αν και η όλο και αυξανόμενη χρήση της τεχνολογίας μέσω των διαφόρων apps επιτείνει την ιδέα του κέρδους, κινήσεις, όπως η πρωτοβουλία της Rozenberg, μπορούν να αναδείξουν ένα κατεξοχήν ουδέτερο μέσο σε έναν μοχλό που θα μας βοηθήσει να σχεδιάζουμε στην πράξη για όλους, χωρίς τις προκαταλήψεις και τα στερεότυπα του παρελθόντος. Ωστόσο, αυτό είναι μόνο μία υπόθεση, που ο χρόνος θα δείξει αν θα επιβεβαιωθεί.

Πηγές/ Further reading

Adam Nathaniel Furman. Outrage: the prejudice against queer aesthetics. Από: architectural-review.com

Elizabeth Wilson. Sexuality and Space edited by Beatriz Colomina. harvarddesignmagazine.org

Pol Esteve. Binary code: technologies of gender. architectural-review.com

Η εφαρμογή Βuilding Without Bias της Hannah Rozenberg στο: building-without-bias.co.uk

.jpg)