Η κλιματική αλλαγή ως έναυσμα μιας γενικότερης μεταβολής;

DS.WRITER:

Ιωακειμίδου Χριστίνα

Πηγή Κεντρικής Εικόνας: who.int

Το Συνέδριο COP26 που διεξήχθη στη Γλασκώβη από τις 31 Οκτωβρίου ως τις 12 Νοεμβρίου του 2021, έφερε για ακόμα μία φορά στο προσκήνιο την επιτακτική ανάγκη μιας ουσιαστικής και κεντρικής απόφασης, με σκοπό την επίτευξη των στόχων που έχουν ήδη τεθεί αναφορικά με την κλιματική αλλαγή. Ωστόσο, το συνέδριο έρχεται έναν χρόνο μετά την ανακοίνωση του Γ. Γ. της Λαϊκής Δημοκρατίας της Κίνας τον Σεπτέμβριο του 2020, Xi Jinping, με την οποία η χώρα δεσμεύεται βάσει πλάνου, να μειώσει την εκπομπή αερίων τού θερμοκηπίου μέχρι το 2060. Η υπόσχεση αυτή περί κλιματικής ουδετερότητας, από μία χώρα που αποκαλείται ως ο «παγκόσμιος ρυπαντής», έρχεται να μεταβάλει, κατά κάποιον τρόπο, την παγκόσμια γεωπολιτική τράπουλα, και ίσως να αναδείξει την Κίνα ως τον ηγέτη της πράσινης μετάβασης. Ποια θα είναι η στάση των υπολοίπων; Θα τη δούμε εν καιρώ.

Από το Κιότο στη Γλασκώβη

Η επιτακτική ανάγκη της μείωσης των παραγόμενων αερίων, και κυρίως του CO2, έχει ήδη εκφραστεί τη δεκαετία του 1970, ενώ μόλις το 1988 δημιουργήθηκαν ο Παγκόσμιος Οργανισμός Μετεωρολογίας και το Περιβαλλοντικό Πρόγραμμα των Ηνωμένων Εθνών (UNEP). Δύο χρόνια αργότερα, η Διακυβερνητική Επιτροπή για την Αλλαγή του Κλίματος, που απαρτιζόταν από 400 επιστήμονες, ανακοίνωσε την πρώτη έκθεση αξιολόγησης, η οποία επιβεβαίωνε τη δραματική έκταση του προβλήματος. Η έκθεση οδήγησε σε αλυσιδωτές αντιδράσεις και την ίδρυση της UNFCCC (Σύμβαση-Πλαίσιο των Ηνωμένων Εθνών για τις Κλιματικές Μεταβολές), που υπεγράφη στη Συνάντηση κορυφής του Ρίο ντε Τζανέιρο, το 1992.

Τον Δεκέμβριο του 1997, σε μία περισσότερο οργανωμένη αλλά συνάμα και δύσκολη προσπάθεια, υπεγράφη το Πρωτόκολλο στη Σύμβαση, γνωστό και ως Πρωτόκολλο του Κιότο. Όλα τα κράτη-μέλη της Ε.Ε. -καθώς και οι περισσότερες χώρες του πλανήτη- επικύρωσαν το πρωτόκολλο, με εξαίρεση τις ΗΠΑ. Η τελευταία, μάλιστα, δικαιολόγησε την αντίθετη στάση της βασιζόμενη στην ανυπαρξία δεσμεύσεων των αναπτυσσόμενων, τότε, χωρών, ανάμεσα στις οποίες βρίσκονται η Κίνα και η Ινδία. Εξαίρεση επίσης αποτελούσαν και οι «καθαρότερες» χώρες, λ.χ. Νορβηγία και Ν. Ζηλανδία, στις οποίες επετράπη ακόμα και η αύξηση των εκπομπών. Το 1997 θα είναι και η χρονιά που θα τεθεί στο τραπέζι, όπως διαβάζουμε στο σύμφωνο, ο όρος τής Εμπορίας των ρύπων.

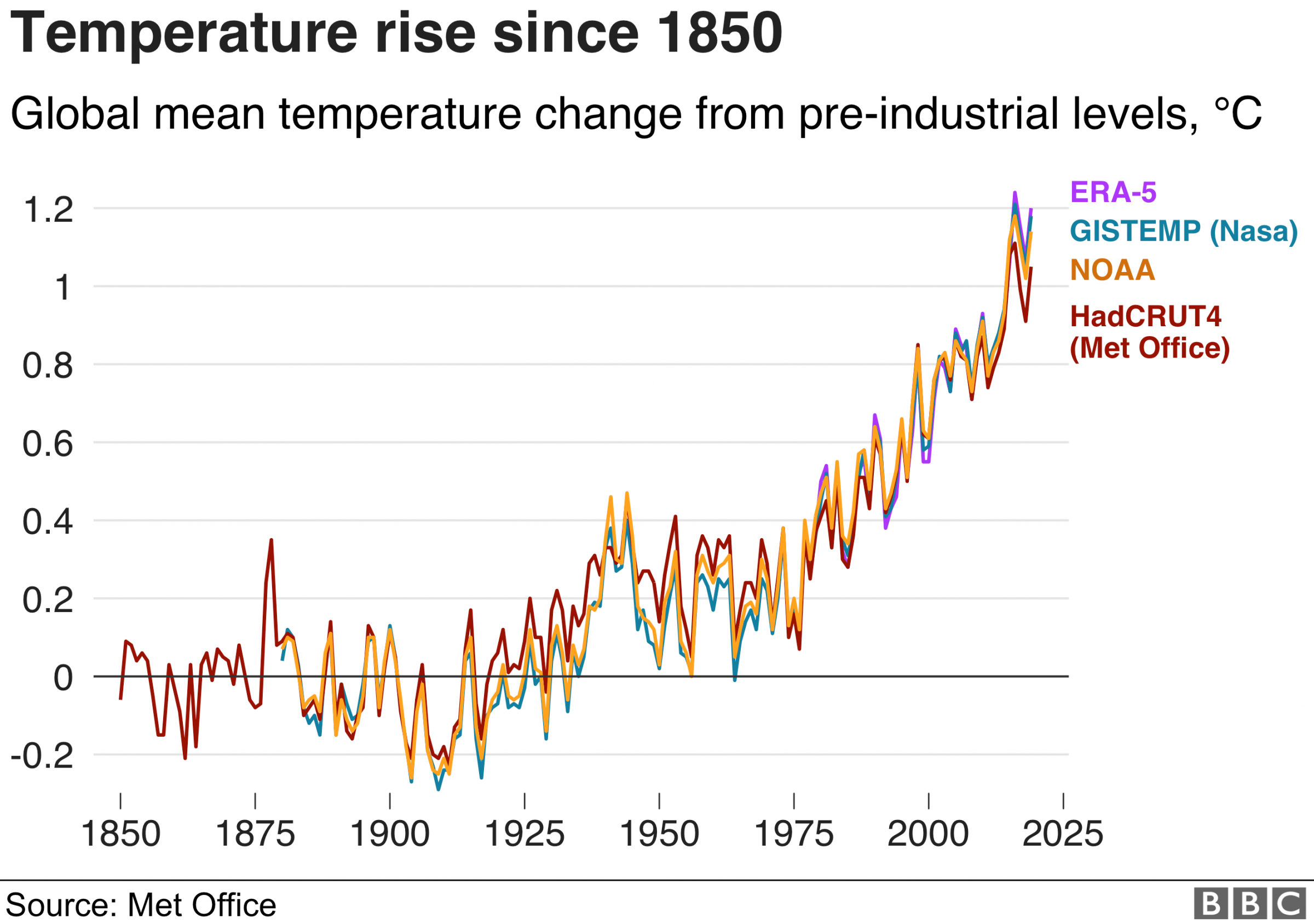

Ωστόσο, και παρά τις δεσμεύσεις ότι το κάθε ανεπτυγμένο κράτος θα έπρεπε να μειώσει κατά 5% τις συνολικές εκπομπές ρύπων από το 2008 ως το 2012, οι στόχοι φαίνεται να είναι άπιαστοι. Παρά τις συνεχείς διαβουλεύσεις και συζητήσεις της επιστημονικής κοινότητας, τα χρονικά όρια στα οποία υπολογίζεται να περιοριστεί η αύξηση της θερμοκρασίας συνεχώς ανεβαίνουν, κάνοντας τις πιο αισιόδοξες προβλέψεις να μιλάνε για περιορισμό τής υπερθέρμανσης το 2050.

Πηγή Εικόνας: ichef.bbci.co.uk

Η πιο πρόσφατη και κάπως αμφιλεγόμενη προσπάθεια συνομιλιών διεξήχθη στη Γλασκώβη το φθινόπωρο του 2021. Η 26η Διάσκεψη για το κλίμα (COP26), αν και αρχικά ελπιδοφόρα, δεν έδειξε να παίρνει ουσιαστικά μέτρα. Η «εξάλειψη του άνθρακα» μετετράπη σε «μείωσή του», με την Κίνα και την Ινδία να βάζουν όριο στο πώς θα πρέπει να αντιμετωπιστεί ο περιορισμός αυτού του, οικονομικά, σημαντικότερου ορυκτού. Δεν πρέπει άλλωστε να παραβλεφθεί, ότι αυτό κινεί οικονομικά και ενεργειακά τον πλανήτη, ταυτόχρονα όμως ευθύνεται για το 40% των συνολικών εκπομπών διοξειδίου του άνθρακα.

To Green New Deal και η Κίνα

«Πώς θα μπορέσουμε να εξαλείψουμε τον άνθρακα όταν πρέπει να αντιμετωπίσουμε τη φτώχεια;». Αυτή η φράση του Ινδού υπουργού περιβάλλοντος, Μπουπίντερ Γιάνταβ, φαίνεται να συνοψίζει το πρόβλημα πίσω από τις μακροχρόνιες διαβουλεύσεις. Η στάση αυτή της Ινδίας και η απαίτηση της Κίνας για επικέντρωση στη μείωση και όχι εξάλειψη των εκπομπών, φέρνει αλλαγή και στην παγκόσμια πολιτική σκακιέρα. Η ανακοίνωση της κινεζικής πλευράς περί σταδιακής απανθρακοποίησης της οικονομίας, έχει εκληφθεί μάλλον με σκεπτικισμό από τις υπόλοιπες χώρες, και κυρίως από τη Γαλλία. Παράλληλα, και σύμφωνα με τον ιστορικό Α. Tooze, τα κράτη-μέλη της Ε.Ε. δεν έχουν λάβει ακόμη αποτελεσματικά μέτρα με σκοπό την περιβαλλοντική βελτίωση, κρατώντας μία περισσότερο «ειρηνευτική» στάση απέναντι στο πρόβλημα. Αυτό είχε ως αποτέλεσμα, η δομημένη πρόταση της Κίνας να δίνει λύσεις στον αντίκτυπο που θα έχει ο όποιος περιορισμός τής βιομηχανικής παραγωγής, εξαιτίας της μείωσης των ορυκτών καυσίμων. Άλλωστε, η σχέση της βιομηχανίας με την οικονομική και κατ’ επέκταση ταξική διαμόρφωση των κοινωνιών, είναι ορατή ήδη μετά το τέλος του Β’ Παγκοσμίου πολέμου.

Ωστόσο, πηγαίνοντας έναν χρόνο πριν την κινεζική απόφαση, το 2019 στις Η.Π.Α., με πρωτοβουλία ακτιβιστών και τη βοήθεια της Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez και του Ed Markey, συντάχθηκε ένα δεκατετρασέλιδο κείμενο, το Green New Deal resolution. Σε αυτό αναφέρονται τα εναρκτήρια βήματα της ενεργειακής μεταβολής και της ολικής αλλαγής, την οποία θα φέρει σε όλους τους τομείς της δημόσιας και ιδιωτικής ζωής. Το κείμενο προσπαθεί να δώσει απαντήσεις στο πώς θα χρησιμοποιούνται οι εναλλακτικές πηγές ενέργειας σε πεδία όπως οι μεταφορές, ο οικοδομικός τομέας ή και η καλλιέργεια. Όμως, και όπως αναφέρθηκε προηγουμένως, η αλληλένδετη σχέση των ορυκτών καυσίμων με την οικονομικοκοινωνική σταθερά των βιομηχανικών κρατών είναι εμφανής. Αν και το Green New Deal έχει ως προτεραιότητα την εξασφάλιση των εργασιακών δικαιωμάτων, την καθολική ιατρική περίθαλψη και την εξασφάλιση θέσεων εργασίας, δεν φαίνεται να δίνει ουσιαστικές λύσεις για το πώς θα αντιμετωπιστεί η αναμενόμενη αύξηση της ανεργίας, στην περίπτωση περιορισμού τής βιομηχανικής παραγωγής. Έτσι, το ερώτημα του Γιάνταβ παραμένει αναπάντητο και σε αυτή την, κατά τα άλλα, ελπιδοφόρα αμερικανική πρόταση. Μένει τώρα να δούμε, πώς η κάθετα σχεδιασμένη πρόταση της Κίνας θα μπορέσει να απαντήσει το συγκεκριμένο ερώτημα.

Ωστόσο, δεν είναι μόνο ο κατεξοχήν βιομηχανικός τομέας υπεύθυνος για την περιβαλλοντική μόλυνση. Σύμφωνα με έρευνα του RIBA, ο κατασκευαστικός τομέας είναι εξίσου υπόλογος, καθώς οι εκπομπές από τα κτίρια φτάνουν το 40% των αερίων του θερμοκηπίου. Πώς μπορεί, λοιπόν, αυτή η υφιστάμενη κατάσταση να αντιστραφεί, και με τι είδους πρωτοβουλίες;

Η θέση της αρχιτεκτονικής και του design

Όπως ήταν αναμενόμενο, η απουσία ουσιαστικών συζητήσεων για τον κατασκευαστικό τομέα κατά τη διάρκεια των διαφόρων διαβουλεύσεων για το κλίμα, έφερε την αντίδραση πολλών αρχιτεκτόνων και designers. Αποφασιστική ήταν η απάντηση πολλών αρχιτεκτόνων και για τις θέσεις τής Διάσκεψης της Γλασκώβης, με τον Andrew Waugh, του λονδρέζικου Waugh Thistleton Architects, να αναφέρει: «Είναι απλώς μία αρχή, τη στιγμή που είναι πολύ αργά». Την ίδια άποψη εξέφρασε και ο Simon Allford, πρόεδρος του RIBA, δίνοντας ο ίδιος μεγαλύτερη σημασία στο μέλλον που θα έχουν οι αποφάσεις της διάσκεψης, ενώ στη φράση «καλύτερο από το τίποτα, όμως σαφώς ανεπαρκές» της Hélène Chartier, επικεφαλής του C40 Cities, ίσως συνοψίζεται η γνώμη των περισσότερων επαγγελματιών του χώρου.

Πώς όμως θα μπορούσε να είναι η μετάβαση σε μια πιο οικολογική προσέγγιση του κατασκευαστικού κλάδου;

Σχεδιάζοντας το μέλλον

Στο βιβλίο του Paul Hawken, Drawdown (2017), διαβάζουμε ότι, εάν το 9.7% των νέων κατασκευών αγγίξει τη μηδενική χρήση ενέργειας προερχόμενης από άνθρακα, τότε και οι εκπομπές αερίων του θερμοκηπίου θα μειωθούν κατά 7,1 γιγατόνους. Η επιτακτικότητα της μείωσης των συγκεκριμένων ποσοστών οδήγησε πολλούς αρχιτέκτονες και designers να αναλάβουν δράση. Χαρακτηριστικό παράδειγμα είναι η απόφαση του RIBA να αναπτύξει το 2030 Climate Challenge, ενημερώνοντας και βοηθώντας τους αρχιτέκτονες, έτσι ώστε να σχεδιάζουν με μια περισσότερο περιβαλλοντικά φιλική ματιά, αποσκοπώντας στην επίτευξη της μηδενικής χρήσης άνθρακα. Οι τέσσερις προϋποθέσεις είναι οι εξής: η μείωση της λειτουργικής ενέργειας και του ενσωματωμένου άνθρακα, η λελογισμένη χρήση πόσιμου νερού, και τέλος η επικέντρωση στην υγεία και την ευεξία των ενοίκων.

Επιπλέον, σε μία εποχή που τα σπίτια γίνονται όλο και μεγαλύτερα, έχοντας περισσότερες ενεργειακές ανάγκες, η μελέτη για την κατασκευή μικρότερων και πιο πρακτικών χώρων θα ήταν μία ακόμα σημαντική λύση, για τον περιορισμό του συλλογικού «αποτυπώματος άνθρακα».

Στο πιο πρακτικό μέρος του σχεδιασμού, η μελέτη για τον -κατά το δυνατόν- φυσικό φωτισμό των χώρων, η καλύτερη μόνωση, η χρήση φωτοβολταϊκών και φυσικού αερίου, ή ακόμα και η υιοθέτηση των «πράσινων οροφών», μπορούν να είναι κάποια από τα μέσα που θα βοηθήσουν στην κατά 70% αποδοτικότερη λειτουργία του κτιρίου, βασισμένη σε εναλλακτικές πηγές ενέργειας. Επίσης, η χρήση φυσικών πόρων όπως το ξύλο ή η πέτρα θα μπορούσε να συμβάλει, σε έναν βαθμό, στον περιορισμό τής χρήσης των βιομηχανικών κατασκευαστικών προϊόντων.

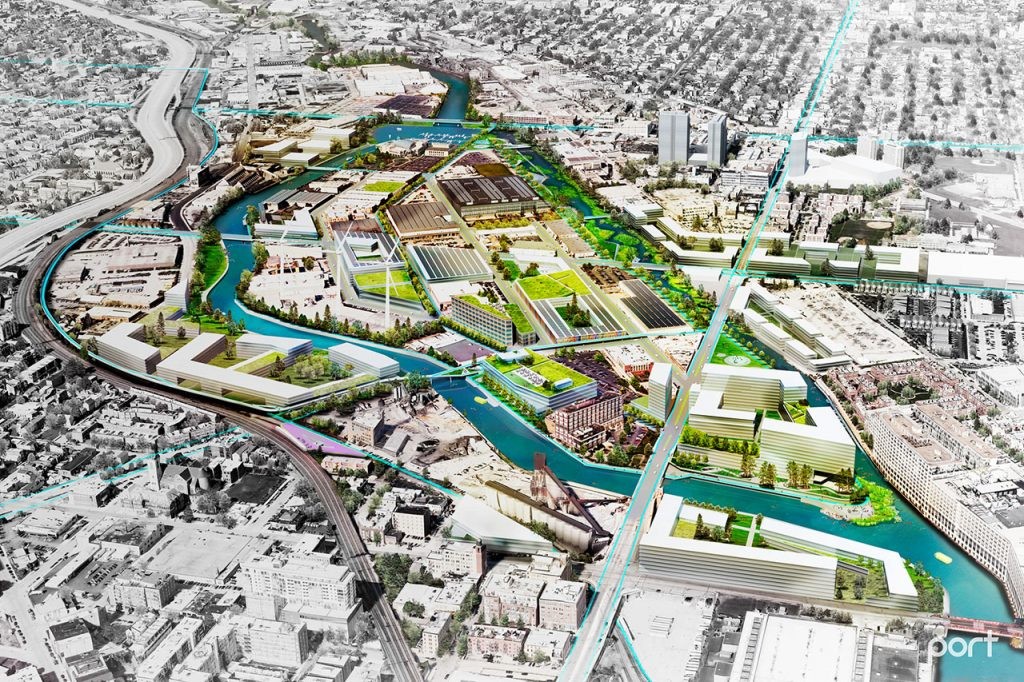

Πηγή Εικόνας: environment.princeton.edu

Τέλος, φυσικά ο καλύτερος αστικός σχεδιασμός, με επίκεντρο την ελαχιστοποίηση της χρήσης των αυτοκινήτων και την παράλληλη επέκταση των πεζοδρόμων και ποδηλατοδρόμων, θα συμβάλει στην προσπάθεια μείωσης της περιβαλλοντικής ρύπανσης. Παράδειγμα τέτοιας αλλαγής είναι η πόλη του Πόρτλαντ στις Η.Π.Α., όπου ο καλύτερος σχεδιασμός έφερε και τον περιορισμό, κατά 20%, της χρήσης αυτοκινήτων.

Αντίστοιχες κινήσεις για μια πιο πράσινη αρχιτεκτονική έχουν γίνει και στην Κίνα, ήδη από το 2017. Η διαφορά με τα προηγούμενα παραδείγματα είναι ότι η κινεζική πλευρά ακολουθεί και πάλι ένα κεντρικά οργανωμένο πρόγραμμα οικολογικής ανάπτυξης, το οποίο υποσχόταν ότι το 50% των κτιρίων που θα κατασκευάζονταν μέχρι το 2020, θα είχαν πιστοποίηση «πράσινου κτιρίου». Στόχος του πλάνου είναι, μέχρι το 2030, η χώρα να αυξήσει τα φιλικά προς το περιβάλλον κτίρια από το 5% (ποσοστό του 2017) στο 28%. Φυσικά, η αποτελεσματικότητα των κατασκευών -τόσο σε ενεργειακό επίπεδο όσο και σε πρακτικό-, σε μία χώρα όπου το ποσοστό αστικοποίησης έχει εκτιναχθεί τα τελευταία 15 χρόνια στο 40%, είναι η πρωταρχική μέριμνα του προγράμματος.

Το αποτυχημένο εγχείρημα του Project Ara

Από την προσπάθεια περιορισμού τής κατανάλωσης ενέργειας δεν θα μπορούσε να εξαιρεθεί ο κλάδος του design. Πολλοί designers έχουν στραφεί σε πιο φιλικούς προς το περιβάλλον τρόπους σχεδιασμού, τόσο αντικειμένων όσο και συσκευών. Από τα ready-made έπιπλα και διακοσμητικά στα ηλεκτρικά αυτοκίνητα, η τεχνολογία δείχνει ότι θα μπορούσε να χρησιμοποιηθεί με τέτοιον τρόπο, ώστε να μειώσει την εκπομπή ρύπων.

Μια τέτοια προσπάθεια έγινε και από την Google με το λανσάρισμα του Project Ara, με τη συνεργασία των εταιρειών LG και Motorola. Εν συντομία, βάσει ενός καινοτόμου σχεδιασμού μέσω Phonebloks, ο χρήστης θα μπορούσε να ανανεώνει το λειτουργικό των συσκευών αυτόματα, προσφέροντας στην εκάστοτε συσκευή καινούριες δυνατότητες. Έτσι θα απομακρυνόταν από τη λογική της αγοράς ενός νέου, πιο εξελιγμένου μοντέλου. Δυστυχώς, παρά την πολλά υποσχόμενη πρόταση και τον θετικό αντίκτυπο που αυτή θα είχε στον περιορισμό κατανάλωσης ενέργειας και βιομηχανικών αποβλήτων, όπως κινητών τηλεφώνων, το εγχείρημα αυτών των DIY συσκευών στέφθηκε με απόλυτη αποτυχία και εγκαταλείφθηκε. Ο λόγος πίσω από την ακύρωση του προγράμματος δεν είναι επισήμως γνωστός, αφού οι εταιρείες δεν έδωσαν μία συγκεκριμένη αιτιολόγηση. Ίσως η αδιαφορία πολλών καταναλωτών αναφορικά με τις εξειδικευμένες λειτουργίες των συσκευών ή ο κοστοβόρος σχεδιασμός τους, να αποτελούσαν κάποιες από τις αιτίες απόσυρσης των υβριδικών αυτών κινητών.

Ωστόσο, η λογική της ανάπτυξης των συγκεκριμένων μοντέλων με σκοπό την αποφυγή τής συνεχούς αγοράς νέων μπορεί να ήταν αυτή που τελικά στοίχισε στην Google, καθώς, αν η πρότασή της πετύχαινε, οι πωλήσεις της θα μειώνονταν κατακόρυφα, αφού, με την προσθήκη μόνο συγκεκριμένων «κομματιών», π.χ. μιας πιο εξελιγμένης κάμερας, δεν θα υπήρχε η ανάγκη ανανέωσης της συσκευής με την αγορά μιας νέας. Αυτό είναι φανερό ότι δεν θα λειτουργούσε προς όφελος των προαναφερθεισών εταιρειών, αλλά ούτε των κατασκευαστών.

Πηγή Εικόνας: cnet.com

Οι παραπάνω κινήσεις, σε συνδυασμό με τις προτάσεις για το μέλλον, αποδεικνύουν ότι λύσεις υπάρχουν, αρκεί να είναι δομημένες, εστιάζοντας πάντα σε εφικτούς στόχους. Αν και ευελπιστούμε ότι οι ατομικές αυτές προσπάθειες θα μπορέσουν να αντεπεξέλθουν στις νέες ανάγκες των σύγχρονων κοινωνιών, δείχνοντας τον δρόμο για έναν καλύτερο τρόπο αντιμετώπισης της περιβαλλοντικής αλλαγής, κατά πόσο αυτές θα μπορέσουν τελικά να αναστρέψουν την ήδη δύσκολη κατάσταση; Πόσο αισιόδοξοι μπορούμε να είμαστε, ελπίζοντας σε ένα καλύτερο μέλλον;

Παραπομπές

-Πρωτόκολλο του Κιότο. Από: ypen.gov.gr.

-Hawken, Paul. 2017. Drawdown. New York, NY: Penguin.

-2030 Climate Challenge. www.architecture.com.

-Charbonnier, P., For an Ecological Realpolitik, Από: www.e-flux.com.

-Designers vs. Climate Change. Από: https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/designers-architects-take-on-climate-change.

-Baker, A., COP26 was "better than nothing but clearly insufficient" according to architects who were there. Από: https://www.dezeen.com/2021/11/17/cop26-insufficient-architects-designers-responses/.

-Αμφιλεγόμενο-φινάλε-για-την-COP26.-Από: https://www.dw.com/el/%CE%B1%CE%BC%CF%86%CE%B9%CE%BB%CE%B5%CE%B3%CF%8C%CE%BC%CE%B5%CE%BD%CE%BF-%CF%86%CE%B9%CE%BD%CE%AC%CE%BB%CE%B5-%CE%B3%CE%B9%CE%B1-%CF%84%CE%B7%CE%BD-cop26/a-59815084.

-Dawood, S., What can designers do to help tackle the climate change crisis?. Από: https://www.designweek.co.uk/issues/29-april-5-may-2019/what-can-designers-do-to-help-tackle-the-climate-change-crisis/.

-Weyl, D., & Hong, M., Lessons from China's ambitious green building movement. Από: https://www.greenbiz.com/article/lessons-chinas-ambitious-green-building-movement.

-TechAltar, Why Have Modular Smartphones Failed? Από: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CcQxdjHlKO4&ab_channel=TechAltar.

.jpg)

.jpg)